18th Battalion Association[i]

Windsor and Detroit Branch

*MEMORIES[ii]*Do you remember that just before Christmas (1915) every member of the Battalion received a nice gift package from the people of Windsor. Inside each package was a card showing the name of the donor. You were supposed to sign the card and hand it back in. As we sat in the M & N [trenches][iii] opening our packages, I can recall that many of the names which were then mentioned as donors were the same name of persons in Windsor today who are still active in the business life of the city.

The card in Jack Lee’s[iv] package showed the donor to be a Miss Mary Wigle. Jack, who could be funny at times, started putting on airs until he learned that some one in sixteen Platoon had received a package with the card showing the same donor. It was proved that Miss Mary had donated more than one of the appreciated gift packages. (A few months later Jack was killed in action.)[v]

Strange as it may seem, we had a fellow in our Platoon who never received a letter or a package (except the one from Windsor) all the time he was with us. Some of us vowed that, if we ever got back to England, we would write him a letter so that he would at least hear his name called when the mail was being distributed. He beat us to it. He was wounded at Sanctuary Wood early in June and I don’t believe he ever returned to the Battalion.

He was a nice person. You would that thought that surely somewhere, there must have been someone who cared.

The Story

This story relates the delivery of gift parcels or packages from the home front to the 18th Battalion during its first Christmas in the front. It relates simply and economically the impact that this act from the citizens from Windsor, Ontario had on two soldiers. One is named, Private Jack Lee, and one is left anonymous.

For Lee, the package comes from Miss Mary Wigle, perhaps one of the daughters of the C.O. of the Battalion, Lt.-Colonel E.S. Wigle. He holds this gift as a distinction until he finds out that another soldier had received a similar gift from Miss Mary.

The other soldier only receives this package and no other. The author[vi] relates how he and some comrades wanted to send him some mail so he was not left out of mail call.

The story ends with a lament for the anonymous soldier not getting any mail from someone who “cared.”

Discussion

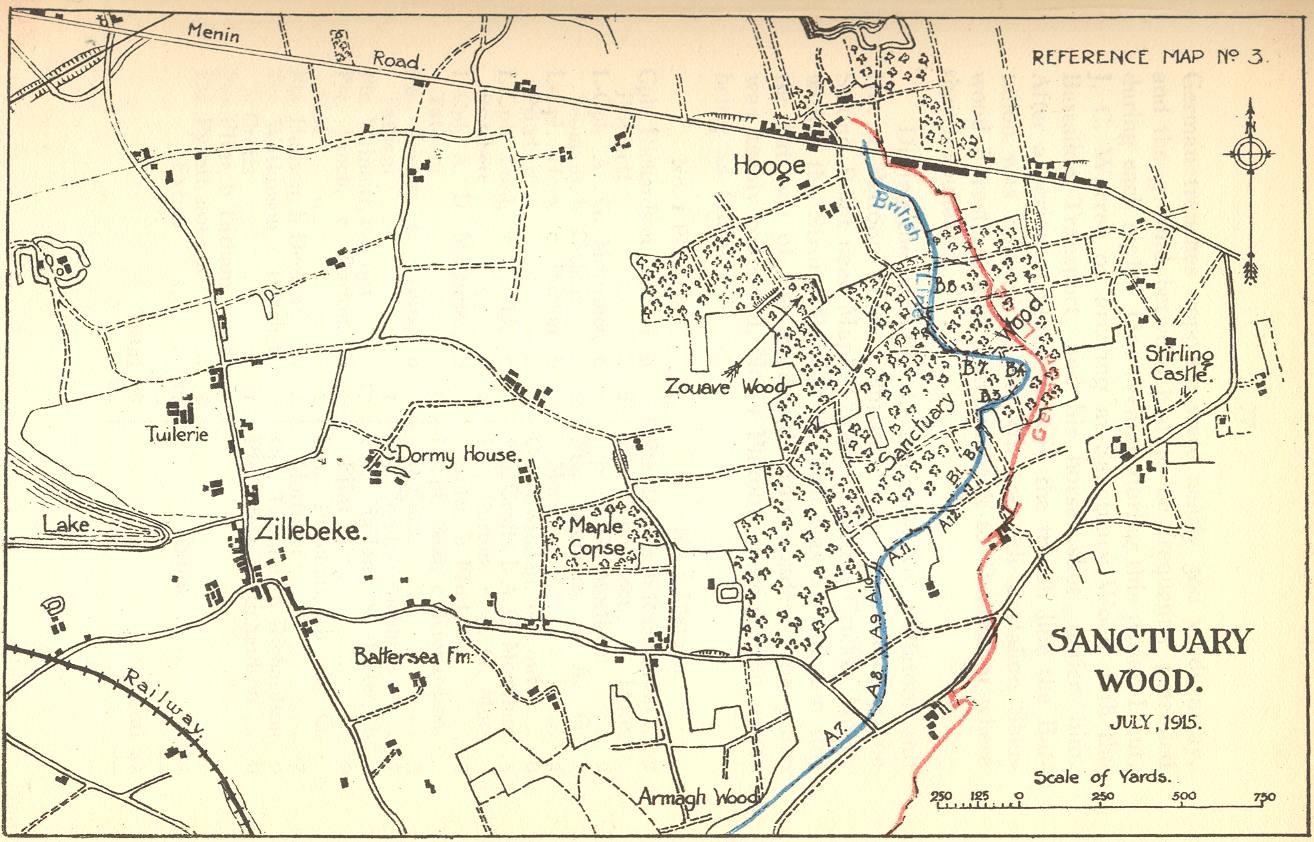

This short story is made poignant by the contrasting fates of the soldiers. Private Lee is named and identified and his “story” has more substance. But he is to die on the first day of battle for the Canadian at the Somme[vii]. He is killed and his remains never identified resulting in his recognition of sacrifice at the Vimy Memorial, along with the other 11,284[viii] other Canadians on the Memorial. There is a photograph of Private Lee. The other soldier, anonymous, is portrayed as being isolated to the outside world of the home-front as he gets no mail, and, then, disappears into the maw of the machinery of war after his wounding at “Sanctuary Wood”.[ix] His anonymity is complete. He is not named so there is no way to follow up on this “memory” to see if he survived his wounds.

The “memory” is almost a lament about home and comradeship. Private Lee seems to be “miffed” at the fact that the attentions of Miss Mary Wigle have been shared by her generous act of creating gift packages for more than one soldier of the Battalion. This apparent jealousy towards another soldier who also received a package is touching and humorous. We can imagine the strong affinity Private Lee would have towards Miss Mary when he received a package from her. For him. Only him. And then, as he brags among the other men of the Battalion in the wet, cold M & N trenches he finds out he is not the only object of Miss Mary’s affections. Other men have received packages, and this makes sense, that if Mary Wigle was the daughter of the C.O. she would not want to share her generosity with one man but with several, as would be appropriate for a daughter of a Battalion commander to do. It ought not to do well for her to appear to curry favour with one soldier.

Comradeship is further expressed by the plan to have other soldiers write the anonymous soldier from England when they got there on leave, or more likely, upon being wounded, to give him some mail so that when mail call is made he is not the only soldier without mail. This plan does not come to fruition as our soldier is wounded before the plan can be implemented.

The “memory” also speaks to the clear delineation between peace and war. The Battalion was in active service in the front for two-and-a-half months by Christmas 1915[x]. It had been subject to its baptism of fire and the relative quiet and safety of this day, Christmas Day, with the packages from home would be a welcome tonic to the soldiers, a reminder of home and family.

Yet, among the comradery of soldiers, men of 18 to 30 years of age, the Christmas packages from the citizens of Windsor may be a reminder of the loneliness and isolation of the soldiers from their homes, especially for the anonymous private.

The “memory” speaks to the larger issue of the support of the home-front in their efforts to supply the soldiers with comforts from home and illuminates a specific event which illustrates the strong social bond between the 18th Battalion and the communities from which it was raised.

How many cards were signed in thanks and returned? I bet Mary’s cards were.

[i] The blog has come into the possession of an exciting and valuable series of documents care of Dan Moat, a member of the 18th Battalion Facebook Group. His Great Grand-Father, Lance-Corporal Charles Henry Rogers, reg. no. 123682 was an active member in the 18th Battalion Association and the Royal Canadian Legion. With is interest in the post-war Association a series of “MEMORIES” in the form of one-page stories relate many of the Battalion’s experiences from the “other ranks” soldiers’ point-of-view.

It appears that the documents were written in the early 1970s, a full 50-years after the end of The Great War and are a valuable social history of soldiers’ experiences as told in their own words about the events that happened a half-century ago to them, and now a full century for us.

[ii] The transcription and research of these “memories” is an attempt to connect and identify the people mentioned in the stories with some accuracy. This is, in no way, a definitive identification of the people in the stories but there is high confidence that these are the men mentioned in the “memories”. In some cases, the story may identify people, places, dates, times, and details inaccurately and, where possible, these details are noted. Given that the men relating these memories would be in there late 70s, at the minimum, their errors can be forgiven. The stories related stand on their own as a social history of the experiences of the men of the 18th Battalion.

[iii] The Battalion was serving near Vierstraat, Belgium during its service in the line during Christmas Day, 1915.

[iv] Lee, John: Service no. 53934.

[v] September 15, 1916.

[vi] C.S.M. Abbott Ross, D.C.M., reg. no. 53187.

[vii] Private Lee was “Killed in Action” on September 15, 1916 during the Battle of Flers-Courcelette. His remains were never identified.

[viii] http://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/history/first-world-war/road-to-vimy-ridge/vimy7

[ix] This reference is to the St. Eloi Crater sector. The Battalion served in the Dickebusch area during the month of June 1916.

[x] There are three blog articles relating to the Battalion’s first Christmas on the Continent. See A Quiet Christmas 1915, No Liberties Were Taken: Christmas 1915 for the 18th Battalion, and Stuff of Legend: The Wounding of Private Dickson on Christmas Day 1915 for more context.