Private Leonard Calvin McMullin was killed May 25, 1918 by a “fishtail” bomb. Yet, the 18th Battalion War Diary makes no mention of this event and it is lost into obscurity. The War Diary Entry for that day: “Working parties again furnished by Bn. for works during the night on trenches. Our party of 1 officers and 12 other ranks constructed trip wires from N.19.2.25.57 to N .19.0.05.50. 2 patrols covered Bn frontage during the night, nothing unusual to report[i].”

This death would pass into history and be forgotten but a mother’s grief and expression of that grief brings Private McMullin’s short life ending in tragedy back to be remembered.

During the night of May 22, 1918, the Battalion relieved the 31st Canadian Battalion at Neuville Vitasse occupying the trenches after the relief was completed at 1.50 a.m. that morning. The tour of duty was initially quite with two patrols covering the Battalion frontage. They reported that outgoing shelling caused casualties at German outposts. On the night of the 24th two patrols covered the Battalion frontage and a small patrol, led by Lieutenant McRae set out to do a reconnaissance. During the patrol the moonlight prevented the patrol to get close enough to a German post to engage it and returned to the lines. Another patrol led by Lieutenant Sheridan tried to engage the post and attack it but the Germans appeared had the advantage of being alerted and a firefight ensued in which the patrol was driven back, without incurring any casualties.

Perhaps this patrol activity initiated a more active posture for the Germans opposite of the 18th Battalion’s position and they used trench mortars to suppress the Canadian lines. Regardless, on this day Privat McMullin was killed by a German “fishtail” bomb as he slept in his “funk hole”.[ii]

This tragic ending to this young man’s life deeply affected his mother for the rest of her life…

Mrs. Irene McMullin of 466 Davis Street, Sarnia, Ontario expressed her grief and sorrow towards the death of her young son and it is this expression that is emblematic of the pain other families and loved ones felt and held close to their hearts as the terrible toll of war scythed its way through the men of the Canadian Corps. Her son enlisted at the at of 17 years and 2 months and was only 19 and a half years old to the day when he died in France.

Perhaps her first expression of sorrow was the following poem[iii]:

Somewhere in France

“Somewhere in France,” so weary, so faithful! “Innocence,” dreaming whilst shells scream overhead;

Dreaming of Home and the Land of the Maple; Knapsack his pillow, the clay for his bed.

“Somewhere” in No Man’s Land! God grant that mother, Never shall dream what we’re bidden to do!

Stake we our life’s blood, but leave for no other. Strenuous deeds which a soldier must do!

“Somewhere,” a mother so lonely is waiting, Craving good tidings from over the sea;

Praying, “O God, should it be Thy good pleasure, Send my darling in safety to me.”

“Somewhere,” in Heaven, past troubles and tears, For a voice, “Come, thou blessed,” in mercy he heard,

‘Neath his cross, khaki clad, fitting garb for our heroes, His dearly loved form now lies undisturbed.

“Somewhere in France” his life work has ended, As o’er parapets gleam the first rays of sun.

‘Twixt boyhood and man, not a score yet of summers! Now peace, grand, eternal – a living “Well done.”

Tho’ poppies may fade, or the lark’s wing grow weary, Mother love – oh so boundless – no living, no end!

Sleep well son! Dear Heart, we ne’er shall forget thee, For thy life thou hast given, for country and friends.

The poem is resplendent with imagery. “Somewhere” there are soldiers, other sons, of mothers and fathers, who are fighting in the trenches of “clay”. They hope and pray that their sons will be safe and “good tidings” will inform them of the continued safety of their kin. But the soldier is called to the ultimate sacrifice with the khaki uniform “fitting bard for our heroes”. She acknowledges his age as he is “Twixt boyhood and man” when he died at 19-year-old. The poem closes with Mrs. McMullin professing her love, which will be eternal and that his memory will not be forgotten.

This poem would not be her only expression of grief. Mrs. McMullin was not afraid to make such an expression in the public sphere.

With time the memories of the war began to fade, at least the specter of the loss of remembrance was possible. The First World War was a cathartic event, one of which the people affected by it would not soon forget. Some people where concerned that appropriate expressions of this sacrifice would not be made, and Mrs. McMullin would make sure that her ideas, if not her need, for an appropriate expression of grief using a monument or statue.

Sarnia was not going to forget its lost sons. Sarnia began its plans for a memorial in November 1918 and was active in eliciting feedback about the nature and form of the memorial. Mrs. McMullin shared her thoughts in a letter to the editor of the Canadian Observer:

Dear Sir,

May I speak for my boy? He is sleeping somewhere in France. I do want to tell you what I believe would please him, could he but speak. For some years prior to enlisting in Lambton’s 149th O.S. Bn., he had taken great pleasure in the public library and the park surrounding it (Victoria Park) and since a memorial to the boys who will never return has been under discussion, my greatest comfort has seemed to centre there, and always I can picture to myself a monument of suitable design, bearing the names of all our city’s fallen heroes, their graves beyond the reach of loving hands to tend and care for, with no mark save a temporary wooden cross.

Reader, have you a boy sleeping over there? If so, does not the little white wooden cross seem a frail thing? And many of our precious boys have not even that much. A granite monument would be a memorial which would withstand the elements for many generations to come and in that way would perpetuate their names as nothing else could. Also it would be something which the residents of our city and visitors as well, would have cause to admire and revere. Furthermore, if this proposed memorial to the boys who have lost their lives should take the form of a home, or a Y.M.C.A. or Y.W.C.A., it would be natural for the original motive to be lost sight of, within a few years.

There are already associations formed for the purpose of bringing comfort and pleasure to the returned heroes. We feel that they can never be fully repaid for their sacrifices and services for humanity. They are deserving of as good as can be produced, but our city and country are prosperous and wealthy, and can well afford to give our beloved dead a separate memorial.

In the years of the future, when one by one our returned heroes have gone to their reward in the Great Beyond, their earthly remains laid to rest beside their father and mother, perhaps, their names and record engraved upon the family monument, or possibly a gravestone of their very own (not only they but you and I together with all others who have known and loved and been loyal to our faithful armies) this proposed granite monument would still stand firm ever beaming the message of peace on earth.

The little white wooden crosses over there seem to send us the message “Do not forget us,” though only wrapped in a blanket, perhaps and buried khaki clad, in a soldier’s grave.

Thanking you, Mr. Edtior [sic] for space and patience, I am

Yours truly,

The Mother of One, Mrs. Irene McMullin, 466 Davis Street.

Mrs. McMullin is polite, almost contrite: “May I speak of my boy?” She elicits his voice through her letter personalizing and bringing to life the reason she wishes the memorial to be places at Victoria Park by the library and one can imagine him at 16-years-old taking “great pleasure” in the stacks of the library, reading and discussing the future. Perhaps he poured over books about the newly developed area of aeronautics brought to the new century by the Wright Brothers. Certainly, as the war began he must have gone to the library to digest the periodicals of the day to keep abreast of the progress of the war, especially during the time of the Miracle on the Marne and other events of the conflict. Private McMullin was only 17-years-old when he enlisted so such memories were not long past for her.

She invokes the loss of others as she asks the readers if they, “…have a boy sleeping over there?” She envisions a monument of granite to “withstand the elements” and notes that other, more socially engaged projects, such as repurposing a building as a memorial, may become obsolete to future needs and their purpose is not dedicated to the act of memorializing the dead. A solid granite structure would bear the vagaries of time and weather better than a building.

She addresses the issue of returned veterans by addressing that they and their families will mark and remember them. But those families that had made the sacrifice of loved ones who were lost and have no marked place of rest or a “little white wooden cross” to mark their graves needs a local and permanent reminder of their loss. The Commonwealth War Graves Committee had an enormous task to quantify, collect, collate and plan for the internment of Commonwealth causalities throughout France and Belgium and such markers that existed were generally of a temporary nature, later to be replaced with the Portland stone headstones now extant at these cemeteries.

No prior conflict had been of such scale. Mrs. McMullin’s response was shaped by her personal loss and that of the larger community. Each village, town, city of Canada had been touched by the war and Sarnia responded quickly to the ethos of grief that mechanized war and its result entailed by offering a definitive concrete expression the community’s grief.

The last image Mrs. McMullin invokes is related to her poem. The boy is “khaki clad” and wrapped in a blanket.

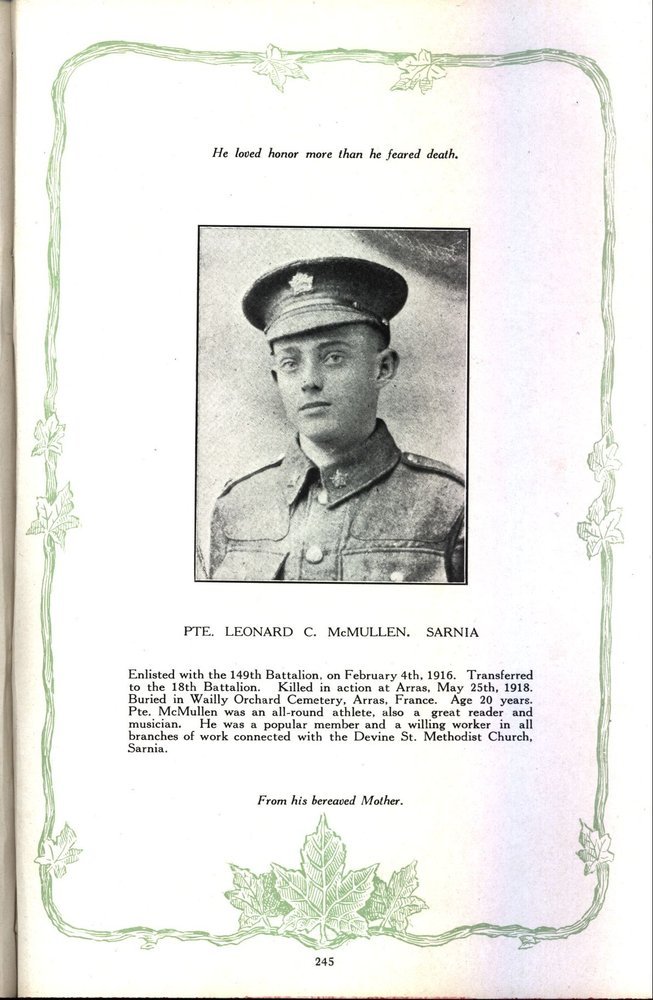

The memorial for Sarnia would be built. Another opportunity to express her loss arouse with the publishing of The Southwestern Memorial Album, published by Sergeant Major Cresswell which lists the men who perished in that region of Ontario and there is a page for Private McMullin. There is a short biography on the page and one would be struck by the youth of the photograph of Private McMullin. The biography speaks to his faith as he was a member, and was commemorated, of the Devine Street Methodist Church in Sarnia.

I

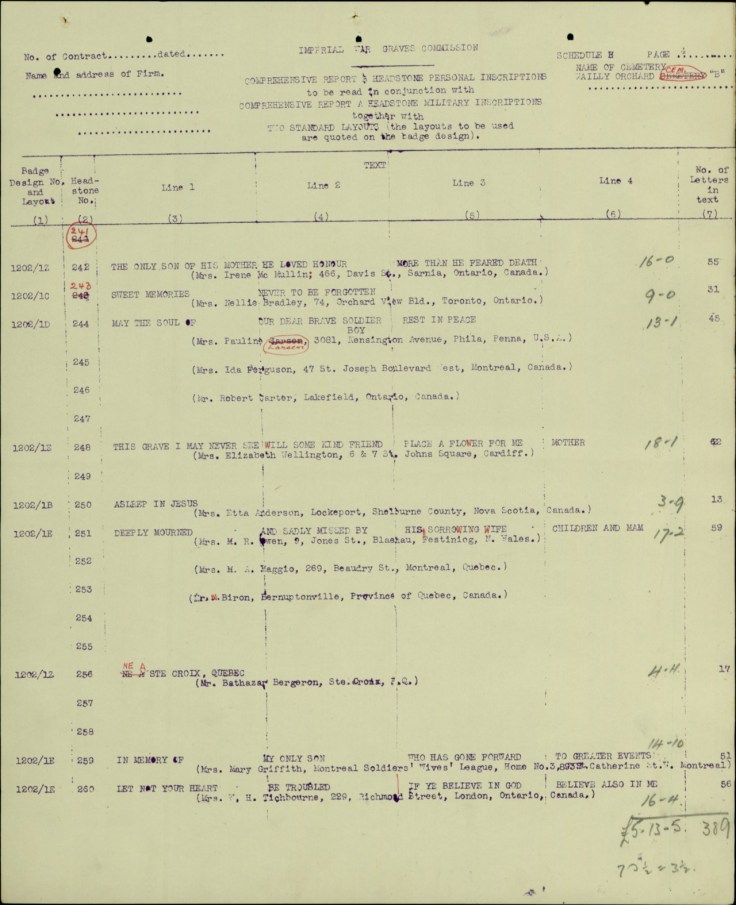

Possibly the last expression of her grief is the epitaph she selects for her son’s headstone. He is buried at the Wailly Orchard Cemetery south-west of Arras, France. The epitaph reads:

THE ONLY SON OF HIS MOTHER

HE LOVED HONOUR

MORE THAN HE FEARED DEATH

It is important for Mrs. McMullin to let others know that he was an only son. This only accentuates the nature of the loss for her and her family. She does not allude to his bravery. She states it clearly – his act of service and the integrity and expression of that service dispels any fear of death and its consequences. This feeling must have been a mutual one as Private McMullin required the consent of his mother to enlist at his age and, probably unknown to him, the British Expeditionary Force’s regulations, which the Canadian Expeditionary Force was subject to, required a soldier to be a minimum of 19-years-old to serve on the Continent in an active combat role[iv]. It is also not the only expression of loss by a mother at this cemetery when one reviews the epitaphs written on the headstones.

Such short words emphasize the power of grief.[v]

Private McMullin is remembered. The work of the Sarnia Historical Society is an extension of the memorial in Sarnia and Mrs. McMullin’s expressions of love through her heart-felt and articulate writing makes our remembrance of Private McMullin accessible over 100 years after he was killed.

[i] Emphasis by author.

[ii] A previous blog article entitled He Loved Honour More Than He Feared Death relates in some detail about Private McMullin’s death. It is ironic and timely that the work of the Sarnia Historical Society led to the rediscovery of this soldier offering the opportunity to re-examine his war experience and the post-war impact of his death to his mother and his community.

[iii] Note that the poem’s format has been kept intact from the source web site. The spelling errors have been corrected to allow for the fluid reading of the poem. The source of the poem is from the Sarnia Historical Society web site. The date of publication, if any, is not known therefore its placement in this order in the article is presumed by the author.

[iv] Holt, Richard. “Filling the Ranks: Manpower in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914-1918.” Google Books, McGill-Queen’s Press – MQUP. Copyright. , books.google.ca/books?id=eQJbDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA71&lpg=PA71&dq=enlistment requirements CEF&source=bl&ots=_EjoklK4Jy&sig=eYsxu_8oobMADy2RqHiwREwi9NE&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjSyfr04O7XAhWF2YMKHQi2CdEQ6AEIeDAL#v=onepage&q=enlistment%20requirements%20CEF&f=false.

[v] Several epitaphs on the Commonwealth War Grave Headstone Production and Engraving document for Private McMullin express similar sentiments. Mrs. Mary Griffiths of Montreal, Quebec expressed her grief with IN MEMORY; OF MY ONLY SON; WHO HAS GONE FORWARD; TO GREATER EVENTS. For more research on the power and variety of GWGC epitaphs please see this web site: Epitaphs of the Great War

Discover more from History of the 18th Battalion CEF, "The Fighting Eighteenth"

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a comment