The soldier sits, relaxed, on a stool. A comrade, face out of frame, leans into him as he sits. He holds a swagger stick, a common affectation of the Canadian troops of the other ranks. The photo is sadly indistinct, and we cannot see the details of his face, but he is looking directly at the camera with a what could be characterizes as a serious gaze, for he is not smiling…

2 years…

2 years is not much time. But for Joshua Watts it made the difference between being a soldier or not. His attestation papers recorded his date of birth to be 29 August 1897. In fact, according to his christening record he was born 2 years later. This would make him 16 years old when he enlisted with the 81st Battalion at Toronto, Ontario on 14 September 1915. Under aged and illegible for service with the army. He got around that with the consent of his mother.

The recruiting officers noted that his apparent age was 18 years old and with his attestation papers properly signed and witnessed the, now, Private, Joshua Watts would begin his military service for the Empire.

His father, Samuel, and mother Maria were fully aware of his son’s actions as he was living with them at 135 Gamble Avenue in the Todmorden section of Toronto. The family had immigrated to Canada prior to 1911 and had established their home in Toronto.

Private Watts now moved in the realm of military men, and, perhaps, he acclimated to this new environment easily having listed his trade as a bricklayer with the Sun Brick Company[i], making him accustomed to hard work and the company of men. His service card for the time spanning 1 October 1915 to April 1916 shows a clean record with no notations of loss of pay or other punishments during this time.

He embarked by train with his Battalion on 28 April 1916 in Toronto and left from Halifax to Liverpool aboard the SS Olympic on 1 May 1916 arriving on 5 May,1916, a fast crossing for the troops.

With this development Private Watts and his comrades must have felt a rush of anticipation as they were closer to experiencing action though this feeling was probably offset with the realization that the 81st Battalion would be broken up for replacements for the active service battalions of the Canadian Expeditionary Forces (CEF) on the Continent at the time.

After just over a month and a half of training at Shorncliffe Camp Private Watts was on his way to join the 18th Battalion arriving at the Canadian Base Depot (Etaples, France) on 29 June 1916 and he was served there for a month before being sent on to the 18th Battalion 27 July 1916 arriving “in the field” 3 days later while the Battalion was in the stationed in the trenches at Trench 28 and Crater ‘B’ near St. Elois, Belgium.

From his arrival in July to August 1916 he would experience the repetitive, boring, but dangerous role of a soldier maintaining a watch and following the rotation of the battalions of the 4th Canadian Infantry Brigade, of which the 18th was a member, as the 18th rotated to and from the front line. The casualties for the 18th in July and August were relatively light with 12 men dying because of enemy action during those months (9 in July and 3 in August).

The now 17-year-old private could not necessarily be counted as “blooded” but with the 18th Battalion’s issue of Lee-Enfield rifles on 20 August 1916 just before it transferred to the Somme signaled a shift to a different pace of deployment.

Things were about to become quite different from the previous month’s service in Belgium.

The CEF was tasked with engaging the enemy in the Somme since the battle had been opened on 1 July 1916. Its reputation probably proceeded itself and many men of the 18th probably rued the day that they enlisted now that they were going to participate in one of the bloodiest battles of the war to date.

On 15 September 1916 the 18th Battalion, along with other elements of the 2nd Canadian Division, fought at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette. The 18th Battalion suffered 94 men killed in action that day. One-sixth of the effective combat strength of the “Fighting 18th” had been eliminated in one day and more would die from wounds later.

For Private Watts his life ended on that day.

For his family this was not to be their experience. The family would not have definitive conformation of his death 18 January 1917. Originally posted missing on 15 September 1916 his status was not changed until 28 November 1916 to “Prev. rep. wd. Now rep. wounded and missing Sept. 15/16.” This update, so long coming after the battle was little comfort to the family and it would not be until 22 January 1917 that the military authorities reported that he was killed in action on that fateful day a Courcelette.

This delay was not helped with an October 1916 Toronto Telegram news clipping reporting as, “…reported wounded and admitted to hospital in France on Sept. 15.” The same paper reported in November that Private Watts was now reported missing with nothing being heard or seen of him since the 15th of September. It then, as the military records show, reports in January 1917 that he is now reported killed in action.[ii]

It is unknown the cause of the delay and without any report from the German authorities of Watts being a prisoner of war the waiting for the Watts family was interminable. His body was found and definitively identified but the Commonwealth War Graves page gives no hint to the location of his body before it was interned at the Adanac Military Cemetery at Miraumont.

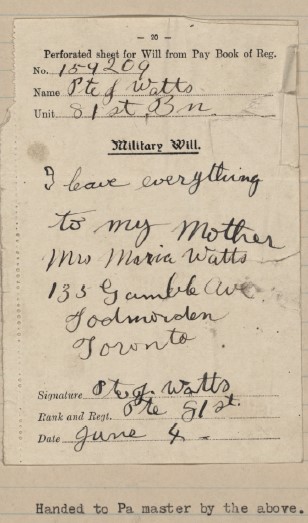

Perhaps Private Watts took some comfort in designating his mother as his beneficiary in his very simple will. It probably did not assuage the grief of his mother.

We will not know the nature of this man’s death. Some comfort can be taken in the knowledge his lies with ten of his 18th Battalion comrades and that countless people have visited this cemetery to reflect and pay homage to all the men buried there.

We know that this man and his family were willing to sacrifice all even though this man was not of age.

The Toronto Telegram reported his age and the family appears to have made no effort to have their son returned to the bosom and safety of the family or to have him sent to England with a “boys” battalion until he was of age.

One indication of this family’s loyalty to the Empire was the statement in one of the news clippings that “His mother has forty male relatives in the land and sea forces of the Empire.”

Perhaps she took solace in the following lines written by Chaplain (Honourary Captain) Harold Dobson Peacock, “He…was proving himself a good soldier. During the severe bombardment which preceded the attack he behaved with coolness and courage, being an example to his comrades.”[iii]

[i] The Sun Brick and Tile Company is recorded in a 1933 Statistics Canada report on the Clay and Clay Products Industry to be located at 1104 Bay Street, Toronto, with a plant in the Don Valley.

[ii] News clippings via the Canadian Virtual War Memorial page for this soldier.

[iii] Toronto Telegram, Circa September – November 1916.

Discover more from History of the 18th Battalion CEF, "The Fighting Eighteenth"

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Excellent as always. Fascinating read. Thank you for sharing this.