The issue of compensation for our service men and women has been a long-standing issue.[i] In the First World War X Canadians were wounded and many stories outline inadequate pension and compensation for the sacrifices they made.

One soldier, Private Donald Roy MacDonald (reg. no. 53709)[ii] was one such man.

Hailing from the Bruce-Huron area of Ontario he enlisted at Clinton, Ontario on 26 October 1914 with the 18th Battalion, making him part of the original draft of this battalion. He was a flour miller by trade. War would change that.

Serving with “C” Company, 18th Battalion, Private MacDonald served with the battalion and was a good soldier. Not exemplary, as he was docked 3-day’s pay for some infraction in January and February 1915 (absent without leave) while the 18th Battalion was stationed in London, Ontario as it began it to train for combat duty.

He arrived in England in late August 1915 and training continued until the 18th Battalion, along with other units of the 2nd Canadian Contingent were sent “overseas” to Belgium, via France, in mid-September 1915.

He learned the “ropes” of active combat during a relatively quiet service in the area south-west of Ypres near Voormezeele, Mount Kimmel, the “Bluff”, and St. Eloi. It was at St. Eloi that Private MacDonald was wounded. On 11 April 1916 the 18th Battalion was at Camp “I” after action new Voormezeele in which the Battalion was tasked in attacking Crater No. 3 as the St. Eloi Craters. A laudatory message was made by the Army Commander for the action so the Battalion was coming off a tough assignment that had, at least, garnered some positive feedback given the outcome of the action was not as expected.

While at Camp “I” the 18th Battalion suffered the death from wounds of Lieutenant P. Lawson, along with 9 other ranks killed, one missing in actions, and 12 wounded. One of those men was Private MacDonald. He had suffered wounds described in a report from No. 2 Canadian Hospital as, “Large lacerated [wound] [right] elbow – shattering lower end humerus and upper end radius.”

Private MacDonald was sent rear for treatment and the efficient casualty clearing service had him admitted to the 4th London Hospital at Denmark Hill on 15 April 1916. The medical notes state:

“Admitted with above large open wound, large part of joint shot away, gas gangrene.

Condition of patient bad.

Rushed one operation to remove piece of recovered bone.

Now very satisfactory.

Should have gentle massage and passive movements.”

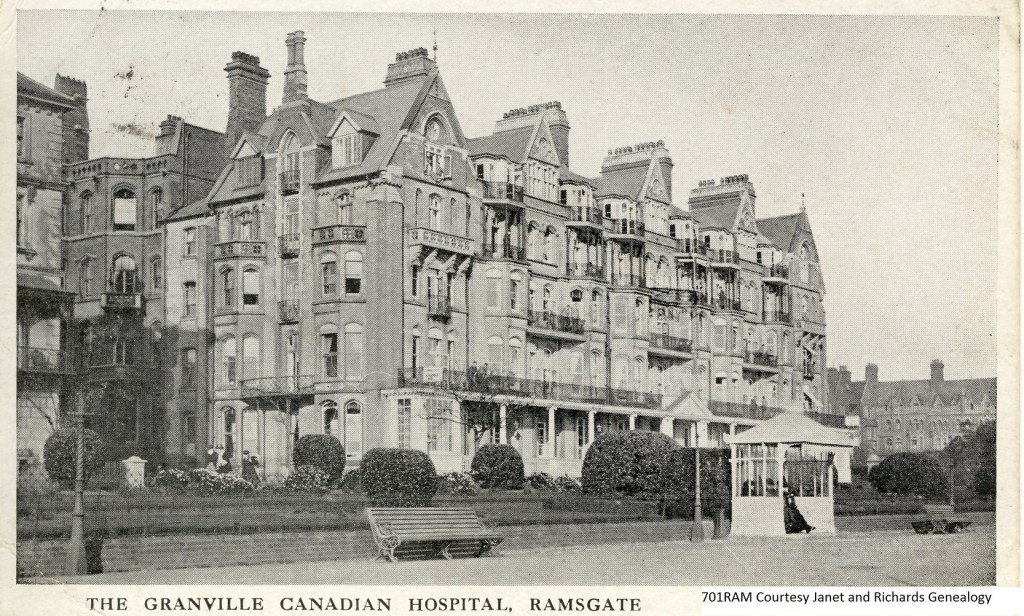

His medical treatment did not stop there as he was sent to Granville Canadian Special Hospital for further treatment, and it was reported that he had needed another operation on 6 July 1916 to remove “remaining bone from elbow”. On 3 December 1916 the medical report for this man recorded that is right elbow was suffering from “COMPLETE ANKLYOSIS” – a condition resulting in abnormal stiffness or complete immobility of this joint.

The next step was to assess the impact of Private MacDonald’s wounds on his life. A board convened on 11 December 1916 at Ramsgate, Shorncliffe Camp recorded that the extent of earning a “full livelihood in the general labour market lessened at present” as being at 50% for six months and 25% “thereafter”. Thus, the Board estimated that his income would be lessened by half for the first six months and then only by a quarter thereafter. Perhaps the Board was assuming some compensatory remedial training or fitment of a device to compensate Private MacDonalds use of his right arm?

He was then returned to Canada to discharge and was stationed at London, Ontario while he waited for discharge. A medical board dated 10 May 1917 reviewed his medical condition and amended the impact of his wounds and their effect on his livelihood was raised to 50% and was permanent and that no further treatment would improve this man’s condition.

Private MacDonald was discharged at London, Ontario on 30 June 1917 as “Being no longer physically fit for War Service.

During June 1917 the Board of Pension Commissioners of Canada indicated that Private MacDonald’s case was being “considered for pension”.

It appears that the Board answered this request with a sum of $8.00 per month.

In a news clipping originating from the Kincardine Reporter and published in The Paisley Advocate dated 25 July 1917 it asks is $8.00 a month is “Adequate For A Returned Soldier Who Loses Right Arm?”[iii]

The article reviews his case relating that he had lost the ability to follow his previous occupation and that the sum granted as his pension “wouldn’t go very far toward keeping a fellow from starving these days.” The article wondered if the board was ‘stingy’ and expressed that this amount of money was not appropriate as it resulted in “men who have risked life and limb should not be properly treated.”

The article expressed that this was not the first case that had come to its notice about veterans not being properly treated.

The now civilian MacDonald is recorded to have moved to Toronto sometime before 1922 residing at 122 Albany Street. Sometime later he moves to the Smith Falls area where he passes on 12 September 1960 having shared his life with Greta Helen Gray. They are buried together at the Maple Vale Cemetery, South Emsley, Ontario.

Further Reading

[i] For background consider accessing “The Origins and Evolution of Veterans Benefits in Canada 1914-2004”

[ii] The news clipping spells his last name as McDonald.

[iii] To put this in context. In 1914 the average wage for male farm help in Ontario was $32.09 ($16.67 for females). Thus, a pension for $8.00 only represented 25% of the wages for an unskilled labourer in 1914. In 1917 the average salary for manufacturing employees was $2,273.00 per annum or $189.42 per month. Thus, $8.00 per month was not representative of a value of an average wage.

Discover more from History of the 18th Battalion CEF, "The Fighting Eighteenth"

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

A very interesting story, so unfair