Introduction

I had the honour and pleasure of speaking at an event held at the Mill Pond Gallery at Cargill, Ontario. The event was to acknowledge the service of the veterans of this proud town by hosting an event that had several speakers talking about the military heritage of Cargill.

I was one of those speakers.

I want to acknowledge the organizers, and in particular Jim Kelley, from whose work[i] I drew my speech for this event. Without his hard work, the many stories of the men and women of Bruce County would be lost to history.

It was a real honour and pleasure to be part of this event.

Speech

Please see the endnotes for more information.

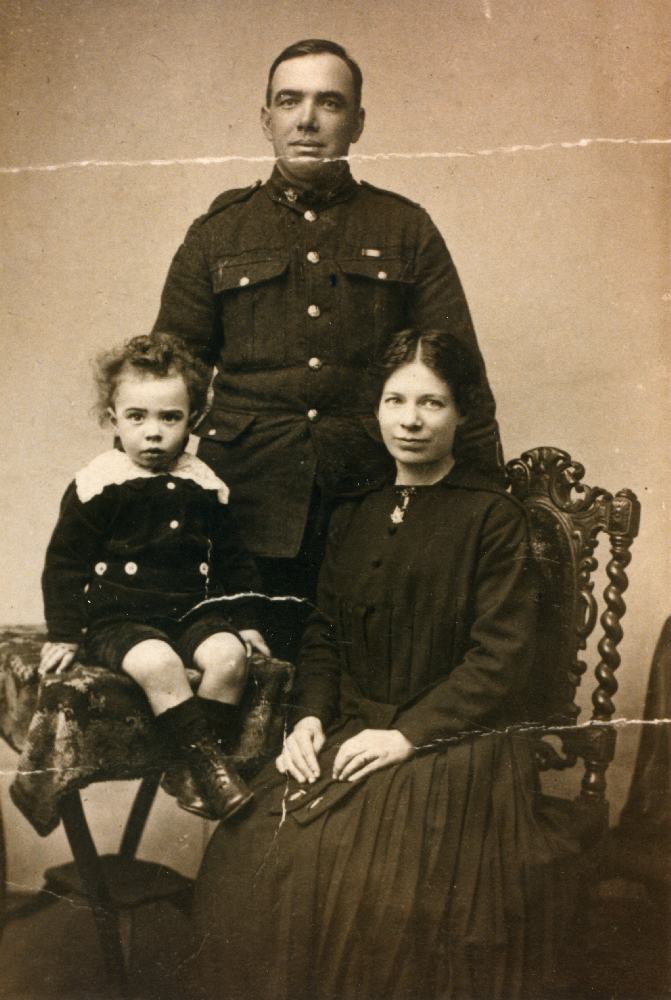

I will be reviewing a letter from Private Alexander Blue[ii] of the 18th Battalion.

He was enlisted close the average age of a Canadian Soldier, at 27 years old. He had life experience to apply to his military service and to his observations about the world around him. He came from a rural farming community, but was a technician, a tinsmith, who would be fashioning and repairing goods for use by agricultural and other industries of the area.

Being the patriotic Canadian, he enlisted in the 18th Battalion just days after it was formed and served with the Battalion at London, Ontario, then West Sandling, Kent, England as it trained up to combat-ready status. He got to Belgium and was in the thick of the war by the end of September 1915 with the rest of the 18th Battalion.

Like many soldiers of armies past, present and future, Private Blue wrote letters, lots of letters. To his father, to the Woman’s Patriotic League, and to others.

It is one of these letters we will examine to help us understand Private Blue. We find out a bit about the man and his service.

Letters offer a window into the world of a soldier better than any other record, save aural interviews, that allow people of the now and future to understand who and what they were – their values and experiences beyond what a history book or war diary offers.

With the work of people like John Kelly, and the other people presenting today, a person can parse the content of a soldiers’ letters in an effort to understand the time, the place, and the soldier more deeply.

In a letter written on 1 April by Private Blue to a Mr. J. J. (Jim) Jacques, Private Blue shares some observations giving us some scope of his experience during the war.

Note that most mail took 2 to 4 weeks to travel from the battlefront to Canada.

To put the letter in context, understand that the 18th Battalion had been in active combat with the 2nd Division of the Canadian Corps in and around Ypres since its arrival in Belgium. It had not been in any major engagements until the action at the Craters at St. Elois, starting April 6th, so the letter had to be written just prior to these events or adjacent,t given some of the content in the letter. We do know the Battalion was in Divisional Reserve at La Clytte, giving the soldiers a measure of safety from German shelling and the opportunity, through passes, to explore the local area.

“Paisley Advocate, April 26, 1916

From the Firing Line

From somewhere in Belgium[iii], Pte. Alex Blue writes to Mr. J.J. Jacques, under date of April 1st.

Just a few lines in answer to your letter about seven days ago on the firing line. Have not had much time for writing, as the weather has been cold and damp, and we were busy watching Heinie. But to-day the weather is fine and getting better all the time, and it is nearly time, for we had a lot of mud to contend with.”

Private Blue is probably relating to the 18th Battalion being in the trenches in the latter part of March, and “A” and “C” Companies were put into Divisional Reserve at Clytte, Belgium. Private Blue was part of Company “C”, placing him very squarely at that location and time.

His comments about the weather are typical and to be expected, and many people may not know that part of Belgium’s water table is high, making the digging and maintenance of trenches challenging for the soldiers in the trenches, especially in wet, damp, and cold conditions

He then shares:

“I was out today looking around and I see the farmers are busy seeding. One thing I noticed in particular was a three-dog team plowing, and only a small boy behind the plow and a larger boy helping the dogs to pull it. As I watched the team going up the furrow, I noticed it was straight as a whip. But the land over here is much easier to work than in Canada. I don’t think it can be beaten for grain-growing, and they sure are good farmers. The land is so full of humus [manure] that if you get a cut or scratch on your hand, you must have it attended to at once or blood poisoning is sure to set in. The horses are the best I ever saw, and it is a treat to see them. I would like a team of them to take back to Canada. Wouldn’t the people stare at them! I would sure take some prizes with them at the fairs. If I didn’t I would think there was something wrong. They are also great dairy people and make good butter. But it costs enough here – 60 cents a pound. And eggs are 5 cents each. I was in an old ruined station one day and noticed a Mellotte cream separator[iv] standing there. And at one point in the firing line I saw an old Massey-Harris rake[v], just in front of my lay – left there in a hurry, I should judge.”

The following paragraph highlights Private Blue’s rural experience and heritage. He is fascinated by the use of dogs to plough a field. The comments show admiration and respect for the quality of the ploughing, and he notes the ages of the people doing the ploughing, the absence of military ages men to be expected in a time of war. The quality of the horses is so very striking, he wishes to take a team home, as they are so good they would be the envy of Bruce County.

The paragraph also gives some context to one of the most important things on a soldier’s mind – food. The expression of the quality of butter and the price of eggs allows us to see the relative cost of food. In 1916, the urban price of butter was $0.40 a pound, and an egg was $0.03, while the price recorded in the Walkerton Telescopes has butter at $0.27 to $0.28 a pound and an egg at $0.02. As a Private,

Blue only earned $1.10 per day. He had assigned $20.00 to his family, making his pay in the field $13.00.

The mention of the Melotte Cream Separator is interesting as it is a Belgian invention that was familiar to Blue, probably as he had exposure to this device in Canada. He also knows the rake produced by Massey-Harris, which is indeed a reminder of home.

The next paragraph relates:

“There were some nice young cattle near the firing line one day, and I [say] if they come up any closer we will have one for dinner. But they didn’t come. They didn’t seem to worry about the “coal boxes”[vi] and “smoke wagons”[vii] bursting about them. And the rats! You never saw the like. You trip over them – and they are so bold. One night in the dugout one of them sunk his claws or teeth into my ear. You should have seen me jump and utter a few words. This country will be over-run with them by the time the war is over, and they are thick around the graves of the boys who have fallen. Another thing we are bothered with is the louse. They are sometimes as bad as the Germans. Say, if you would come around some nice warm day, you would see the boys hunting for them. But no one worries.”

This paragraph is self-explanatory. It vividly shares some of the vermin a soldier would have experienced in the trenches, and the casual attitude towards a common hardship that all soldiers shared throughout history. The reference to the rats near the graves of the fallen is particularly macabre.

The reference to the “coal boxes” and “smoke wagons” refers to different types of German artillery shells, which, depending on their calibre and chemical composition, would explode in a unique manner, giving to the observer the calibre and type of shell. A more common example is the “Whiz Bang,” which referred to a German 77 mm shrapnel shell which was timed to explode above the ground as an airburst to scatter deadly metal projectiles at its targets.

The last paragraph in the letter shares:

“Well, John, we’ve had a couple of good scraps since coming out, and I’m going to tell you the Germans have not much use for us. In both scraps we took quite a few prisoners, who are mighty glad to be made prisoners of war. Some come from Detroit and others from Toronto and some of them can talk as good English as I can. One of our scouts or snipers was talking to a prisoner with whom he had been personally acquainted before the war. The Germans had come down from Verdun for a rest, as they thought, but I guess it was for a scrap. Well, we got there first and got a couple of lines of trenches, which was easy. You can tell the 160th[viii] not to worry, as they will have some fun out here yet. I had some souvenirs, but did not bother carting them around, as we have enough to carry. The only souvenir I want to take home is myself. But a man knows not the hour or minute out here. Tell father I received the parcel yesterday and was mighty glad to get it. I see John Beaton[ix], Jack Devine[x] and Harold Marshall[xi] have enlisted. Well, they deserve credit. Gordon Daniels[xii] is fine and Jack McDougall[xiii] is just the same old Jack. Tom Babcock[xiv] was up to see us to-day. He is in a trench mortar battery out here. Andrew (Babcock[xv]) is Sergt. of the transport, and Sammy Tooke[xvi] is in the transport column. All the boys are fine.”

This paragraph is interesting but not very illuminating when comparing the story Private Blue relates in conjunction with a review of the 18th Battalion’s military experience from September 1915 until 1 April 1916. The battalion was mainly involved in “routine” assignments, rotating from the front line to the brigade reserve and divisional reserve. The War Diary does not note any significant operations during time, except to note some instances involving units adjacent to the Battalion. In other words, no major operations occurred during the time frame of Private Blue’s service, though that would change with the action at St. Elois Craters, and later, the Somme, Vimy, Lens, Passchendaele, and the Last One Hundred Days.

To put a hard comparison, the casualties reported (DOW and KIA) for the months of October, November, December, January, February, and March were 7, 9, 7, 5, 3, and 19, respectively. The 19 casualties reflect increased German shelling in preparation for Spring Offensive actions. To put some context on these loss rates April 1916, when the 18th Battalion fought at St. Elois, that action resulted in 29 dead for the month of April 1916, compared to the 111 suffered at the Somme in September 1916, and 131 men during August 1918.

I surmise that he is relating third hand accounts from other Canadian and Imperial Battalions based on other operations, except, of course, the sniper story.

Certainly, the direct mention of the 160th Battalion gives rise to the awareness that he was being fully informed about the recruitment efforts in Bruce County by post and newspapers sent to him at the front. It shows his strong affiliation to his place and time and is a recognition that the war needed to be continually fed by more personnel and material. His friends and acquaintances are joining, and his positive outlook expresses his patriotism and will to fight, even after 6 months of unremitting exposure to trench warfare. He also takes time to assure those at home that other men of Bruce County currently serving are safe.

What does this letter tell us?

It tells us that Private Alexander Blue was educated and wrote a lively, descriptive letter. Remember, these letters had to pass the censorship of an officer in his Company, so the contents were “family friendly” as it were. They still offer more than a glimpse of our man. He loved so to share his interest in the industry of his place and time – Agriculture – to whom the audience he was writing to was fully aware.

There is a tone of a man confident in success. He is not dour in his description. If anything, he is upbeat, positive, and open to using a little shock value to capture his audience such as sharing the lesser details of trench life – that of rats and lice.

Private Blue would write many more letters, and taken in their totality, give us a glimpse of the man and his times that are much more illuminating that a YouTube documentary.

[i] Kelly, J.C. (2025) LETTERS FROM OVERSEAS: Bruce County and the First World War. 2nd edn. Edited by C. Siekierko.

[ii] Private Alexander Blue. Regimental no. 54004. Several blog articles relating to this man’s service are available.

[iii] Private Blue was in Divisional Reserve at La Clytte (De Klijte), Belgium at the time of the writing of this letter.

[iv] Link with information about this product.

[v] This catalogue shows some of the products available from Massey-Harris. It is interesting to see the reach of Massey-Harris with these Canadian products being sold and used in Europe.

[vi] “Coal Box” probably refers to a 5.9” German howitzer shell.

[vii] Specifics about this shell type were not found.

[viii] Reference to the 160th Bruce Battalion raised in Bruce County. There is an excellent group about this Battalion on Facebook.

[ix] Private John “Jack” Beaton, reg. no. 651446.

[x] “Willian “Jack” John Devine, reg. no. 651762. Served with the 18th Battalion.

[xi] Private Harold Edwin Marshall, reg. no. 651763.

[xii] Private Gordon Jackson Kerr Daniel, reg. no. 53024.

[xiii] Sergeant John “Jack” Alexander McDougall, reg. no. 53253.

[xiv] Private Thomas Babcock, reg. no. A2463. Killed in Action.

[xv] Lieutenant Andrew Enos Babcock, reg. no. 53989.

[xvi] Private Samuel Harold Leslie Tooke, reg. no. 54052.

Discover more from History of the 18th Battalion CEF, "The Fighting Eighteenth"

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Eric Do you mean my cousin Jim Kelly “letters from home”?

On Sun., Nov. 2, 2025, 6:55 p.m. History of the 18th Battalion CEF, The

Yep, and I will fix that! Sorry.

Perfect!

On Sun., Nov. 2, 2025, 7:41 p.m. History of the 18th Battalion CEF, “The

Yep, and I will fix that! Sorry.