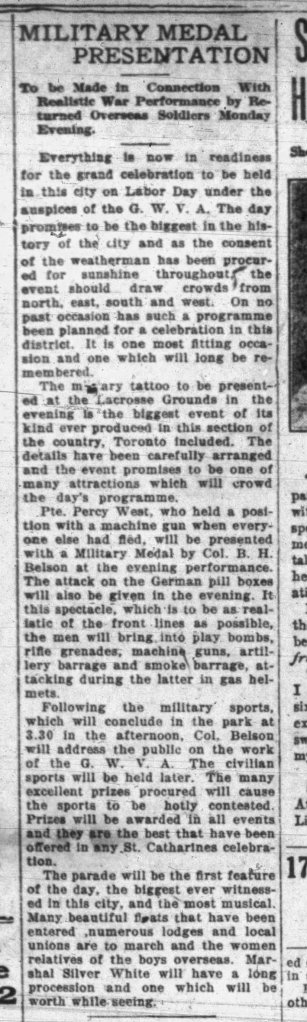

On 2 September 1918, Colonel B. H. Belson would present a Military Medal[i] to a former 18th Battalion soldier, invalided home due to illness as he was discharged from service at Toronto, Ontario, on 15 April 1918.

The circumstances of the act of valour from which he earned his medal speak for themselves:

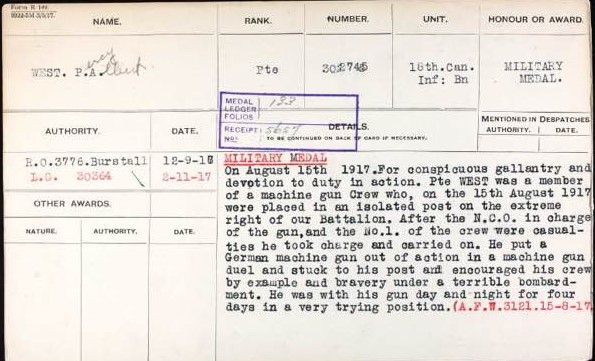

“MILITARY MEDAL

On August 15th 1917.

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty in action. Pte WEST[ii] was a member of a machine gun [Lewis gun] Crew who, on the 15th August 1917 were placed in an isolated post on the extreme right of our Battalion. After the N.C.O. in charge of the gun, and the No. 1 of the crew were casualties he took charge and carried on. He put a German machine gun out of action in a machine gun duel and stuck to his post and encouraged his crew by example and bravery under a terrible bombardment. He was with his gun day and night for four days in a very trying position.

(A.F.W. 3121. 15-8-17.)”[iii]

This “mountain” of a man, at 5’ 2.5”, 132 lbs., fought in more than trying conditions, and earned a medal well deserved.

The only problem was that the article published on 31 August 1918 implied cowardice of other members of the 18th Battalion, as it claimed, “Pte. Percy West, who held a position with a machine gun when everyone else had fled…”[iv]

It is not clear how this statement was corroborated, that the author’s conclusion that soldiers “fled” in the face of the enemy was in stark contrast to the bravery of Private West, making this observation even more onerous to the men it implicated as cowards.

The Lewis Gun was a crew-served weapon that radically changed the face of the infantry platoon in the Imperial Forces. The Lewis Gun, an American invention, was adopted by the Imperial Forces starting in October 1915 to supplement the allocation of Vickers Machine Guns. It was slowly introduced to line battalions, and instead of replacing the Vickers Gun, a heavier weapon with the ability to sustain machine gun fire, due to its water cooling, the Lewis Gun was adopted at the Company and then the Platoon level as a force multiplying weapon to offset the German advantage of light and medium machine guns. The Germans had, initially, the same number of machine guns per unit as the British but employed them more effectively. As the war progressed, so did the role of machine guns.[v]

From the description of the action in the Military Medal citation, it is possible that the role of Private West was that of…

‘World War I broke out in Europe shortly after the Lewis production began. There were no other arms in the Allied arsenal comparable to the Lewis, and it immediately gained an enviable reputation as an effective and reliable light machine gun. To take advantage of the Lewis’ portability and firepower, the British formed infantry machine gun killer teams to eliminate German machine gun emplacements. These teams were used with notable effectiveness, due in no small measure to the lethality of the Lewis. The Germans reportedly attempted to capture, and use, as many Lewis guns as possible and gave the gun the nickname “Belgian Rattlesnake.”’[vi]

https://tacticalnotebook.substack.com/p/german-use-of-lewis-guns-1917

For reference, in 1917, military doctrine in the use of the Lewis Gun required a crew of six. Number 1 was the gunner, usually a Lance-Corporal, and this soldier oversaw the crew; he was responsible for directing the gun, cleaning and maintenance of the weapon and carrying two magazines. Number 2 was responsible for the spare parts and two bags of magazines. Number 3 brings up ammunition and is responsible for the supply of ammunition to the gun. Numbers 4, 5, and 6 carried ammunition and filled and prepared the magazines, as well as acting as a replacement for numbers 1, 2, and 3 if they were put out of action.[vii]

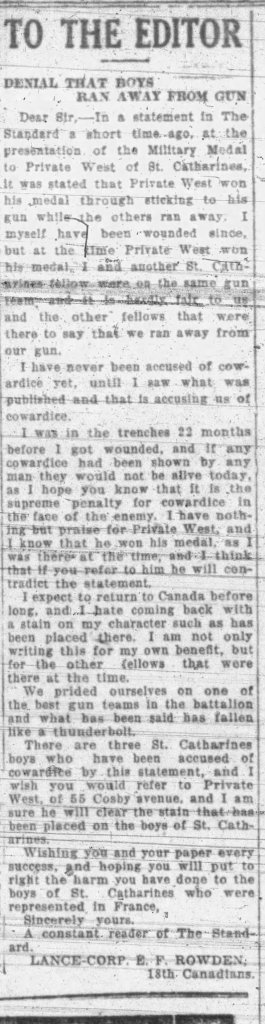

One soldier who was part of the action was not at all pleased with the article published on the 31st of August. Still in the trenches, Private Rowdon[viii] appears to have stewed on the contents of the article until he felt he had to respond.[ix] This he did, and on 23 December 1918, The Standard published a letter in which Rowdon clearly states that no one fled during the action from which Private West earned his Military Medal.

The delay in response by Private Rowdon may simply have been the time it took for information to travel during World War 1. Many soldiers received their local newspapers through the mail with an approximate 2-to-4-week lag from the time the post was made in Canada until reception overseas. Thus, Private Rowdon received the newspaper published on 31 August 1917 and read about the incident 2 to 4 weeks later. There is no accounting for the delay in the reply from Private Rowdon, but using the same timing, and if the newspaper published the letter the day after it was received, Private Rowdon probably wrote the letter at the beginning of December 1918.

Private Rowdon, a witness to the action, would not have anything to do with an article casting aspersions against the men of the 18th Battalion and from St. Catherines – There were no cowards.

He wrote a scathing letter[x] to the Editor of The Standar,d published clearly stating that there were no acts of cowardice during the action. This fact was supported by a letter to the Editor published five days after Private Rowdon’s letter by Private West categorically stating there was no cowardice displayed by the men manning the Lewis machine gun. West praised and thanked the “boys who stood by me during 11 months’ fighting, particularly at Hill 70.” In addition, he states that information about the men fleeing “was not sanctioned by me, neither do I know from what source that information came.”

In Private West’s response he also writes that he hopes the newspaper will give him “space in your columns to reflect on the deserving credit on the lads who were with me at the time I won my Military Medal.”[xi]

There appears to be no retraction or apology from The Standard, and the source of the information is never revealed. Such a claim was very serious, and it is curious that the newspaper wrote something like this, which would, understandably, raise the ire of the men involved. In fact, if true, these men could be subject to court-martial, which could lead to the death penalty.[xii]

However, it appears that Private West did not follow up with letters to the Editor, or at least, they were not published. By this time, the war had ended, and the focus of the newspapers reverted to those items that it reported during peacetime.

The news clipping and resulting letters to the editor illustrate some interesting insights.

The civic pride and the bombastic claims of attendance of an event at St. Catherines, compared to Toronto. The population of the former was 1/26th of that of the latter, according to the 1921 census.[xiii] There certainly was patriotic fervour as the event was well attended, though a follow-up article published 3 September 1918 does not make any estimate of crowd size.

It also shows a recurring issue with news reporting – the embellishing of an article with unsubstantiated claims to increase the drama of the article. There is simply a statement with now corroborate to back up the claim that men fled in the face of the enemy during the action from which Private West would earn a Military Medal.

It simply never happened.

This is confirmed, not only by Private West’s letter, but by another party who was intimately involved with the action in question, Private Rowdon.

Perhaps the unknown author of the originating news article did not understand the implication of accusing soldiers of cowardice during a time of war, but this is unlikely. The author took a statement out of context or made the event up. These short words cast an aspersion on the men of the 18th Battalion and Privates West, and Rowdon took timely efforts to quash the very notion that the men in Private West’s Lewis Gun Team could, or ever would be, cowards.

Rowdon, like West, survived the war, and it is not known if they met after the war to reminisce about the action from which West earned his medal. Rowdon lived until 1959, while West lived the ripe old age of 80, passing away in 1963.

Both men shared an experience which should not have required them to defend their honour. They did, correcting a malicious statement which cast doubt on the bravery of the soldiers of the 18th Battalion.

[i] The (St. Catherines) Standard. 31 August 1918. Page 7.

[ii] Private Percy Albert West Military Medal, reg. no. 3027754.

[iii] London Gazette. Sup. 30364. 20 October 1917. Page 30364.

[iv] The (St. Catherines) Standard. 31 August 1918. Page 7.

[v] Machine guns WWI: Issue, organization and Doctrine – War History. warhistory.org. (2021, July 11). https://warhistory.org/@msw/article/machine-guns-wwi-issue-organization-and-doctrine

[vi] Association, N. R. (2021, August 15). The American lewis gun. An Official Journal Of The NRA. https://www.americanrifleman.org/content/the-american-lewis-gun/

[vii] Foster Groom and Company. (1917). Gun Drill for the Lewis Automatic Machine Gun. In Instruction on the Lewis Automatic Machine Gun (3rd ed., pp. 52–54). essay. Retrieved January 18, 2026, from https://archive.org/details/instructionlewisautomaticmachinegun1917/page/53/mode/2up.

[viii] Private Edward Thomas Rowdon, reg. no. 301720.

[ix] The (St. Catherines) Standard. 28 December 1918. Page 8.

[x] The (St. Catherines) Standard. 23 December 1918. Page 8.

[xi] The (St. Catherines) Standard. 28 December 1918. Page 8.

[xii] Military crimes 1914-1918 british army. The Long, Long Trail. (2016, July 26). https://www.longlongtrail.co.uk/soldiers/a-soldiers-life-1914-1918/military-crimes-1914-1918-british-army/

[xiii] Canada, S. (2008, March 31). Canada year book (CYB) historical collection. Urban centres with populations of over 30,000, 1941 compared with census years 1871 to 1931. https://www65.statcan.gc.ca/acyb02/1947/acyb02_19470103004b-eng.htm

Discover more from History of the 18th Battalion CEF, "The Fighting Eighteenth"

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a comment