Sometime in the early spring of 1915 a young man from Pennsylvania with gainful employment with Ingersoll-Rand as a draughtsman took a trip to Philadelphia to inquire with the British Consulate on how best to pursue an engagement with the Imperial Forces so he could participate in the war. The advice led him, with four other men, to pursue enlistment with the Canadian Forces. Harold Van Allen Bealer, late of Easton, Pennsylvania travelled to Montreal, Quebec and volunteered with the 42 Battalion – The Royal Highlanders – on April 19, 1915.

From that moment he was to experience the war in its fury that it took his life by his own hand.

Private Bealer was almost a typical recruit during this time, other than his American heritage, as he stood 5’ 8” tall with a fair complexion, blue eyes and brown hair. At 140 pounds he was 10 pounds lighter than the average. His service record shows his martial skills to be above average.

Private Bealer was a dutiful son having allocated $20.00 of his pay per month to his mother as well as assigning his will to her.

The 42 Battalion arrived in Plymouth June 19, 1915 and trained at Shornecliffe until it was dispatched to the Continent on October 9, 1915. Within a month Private Bealer was promoted to Lance-Corporal with follow on promotions to Corporal in April 1916; Acting Sergeant June 1916; Sergeants August 1916, and then returns to the Canadian Brigade Depot in February 1917 to Shorncliffe, England where he was granted the commission to Lieutenant.

During this time, he was wounded and participated in a series of actions from which he earned the Military Medal and the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

On September 17, 1916, Sergeant Bealer was wounded during action at the Somme. The Canadian participation in this action started on the 15th and the 42 Battalion was fully engaged. From September 15 to the 17th the battalion suffered 473 casualties. 73 of those casualties where confirmed killed in action; 290 wounded, and a further 66 missing and fate undetermined. His service record indicates a gunshot wound to the back (G.S.W.), yet later reports indicated that he suffered shrapnel wounds to the back (as was noted in a comment below it is probable that G.S.W. is a generic term relating to any wound caused by a projectile.). Regardless, the severity of the wounding but him out of action until his return to his battalion on November 28, 1916.

By December 1916 the 42 Battalion had moved from the Somme to Neuville-St-Vaast in the Pas-de-Calais area and it was at this location on January 1, 1917 that Sergeant Bealer actions were record in the war diary[i]:

At 1.55 am. an organized raiding party consisting of Lieuts. MacNaughton and Martin, Sergts. Bealer, Smith, and Corporal Plowe, Ptes. Maquard, Sedgwick, Richardson and Hepburn left Common Sap Lieut. MacNaughton went out in advance and placed a covering party of bombers about five yards in front of the German wire in the centre of the gap between Common and Birkin craters. Lieut. Martin, followed by Sergt. Bealer, Sergt. Smith and Pte. Maquard, and on reaching the covering party they were joined by Lieut. MacNaughton. The party then proceeded round the lip of Common Crater. They worked their way through the enemy wire and entered his trench at approximately S.28.a.45,948. They proceeded along the trench for a short distance, and on account of the mud being so heavy it was decided to split the party, and move along the parapet and parados. Lieut. MacNaughton and Sergt. Bealer followed the parados, and Lieut. Martin, Sergt. Smith and Pte. Maquard the parapet, until they got to a point near a junction with a communication trench immediately to the right of Birkin Crater where an enemy post was suspected. After waiting at this junction for about 20 minutes, two enemy sentries were observed, one in an improvised shelter, the other in the trench, the latter a moving patrol. As the sentry approached the raiding party, Sergt. Bealer slipped into the trench, held him up at the point of a revolver and forced him to surrender. At the same time Pte. Maquard assuming to be the Sergt. Major called the second sentry from his shelter. The latter came to the entrance and finding himself surrounded dropped his rifle, and threw up his hands. The party then proceeded back and reached our trenches with two prisoners at 3.05 am. Without casualties. Both prisoners belonged to the 23rd. R.I.R.

The 42 Battalion War Diary also related Sergeant Bealer’s awarding of the Military Medal (M.M.) on January 12, 1917 and then the Distinguished Conduct Medal (D.C.M.) on February 17, 1917. The London Gazette records[ii]:

418710, Sjt. H.V.A. Bealer, Can. Infy.

For conspicuous gallantry in action. He carried out a successful reconnaissance and obtained most valuable information. Later, he repeatedly carried messages under have fire. He was severely wounded.

The award citation gives some indication of the martial abilities of now Sergeant Bealer. This brief paragraph, coupled with his rapid rise in rank and mention in the war diary for the raid on January 1, 1917 only hints at the type of soldier Bealer was and how his service was appreciated by the officers and men of the 42 Battalion. The awarding of two medals in such close succession in time is another indication. The awarding of the M.M. was quite common and, in some cases, rather haphazard and indiscriminate, but the D.C.M. is the second highest order of bravery after the Victoria Cross. Therefore, the London Gazette record of this award does not begin to reflect the acts Bealer carried out in order to be distinguished with such an award.

His efforts as a soldier were further recognized when, on February 2, 1917 he was transferred to the Canadian Brigade Depot in Shorncliffe, England to be commissioned as a Lieutenant and taken on strength with the 20th Canadian Reserve Battalion[iii] in Shoreham.

The transition from a front-line fighting soldier to one relegated to training troops for active service may have been at odds for Lieutenant Bealer. His service record begins to show that this service in England led to behaviours which affected his health and his finances. His service record only hints at what transpired.

We do know that about March 15, 1917 he becomes “sick” and that he “carried on” until he entered Cherry-Hinton, an army hospital in Cambridgeshire[iv], for the treatment of venereal disease, specifically gonorrhea. He is treated and the medical board report on September 3, 1917 indicates that he is cured as the “usual tests are negative.” During this time his promotion to temporary Lieutenant is gazetted on May 17, 1917. It appears from his service record that he was admitted and stayed in hospital from March until September 1917 continuously.

On September 1, 1917 Lieutenant Bealer was discharged from Cherry-Hinton with the determination that he was fit for Home Service without marching for 1 month while not being fit for General Service. He stopped his assigned pay of $20.00 to his mother completely. The service records give no indication as to why but his relative base pay had doubled from $1.00 per day as a private to $2.00 per day as a lieutenant, exclusive of field allowance (10 cents and 60 cents per day respectively). From past service records the cancellation of assigned pay to family members was rare so some circumstances compelled Lieutenant Bealer to cancel this portion of his pay to his mother.

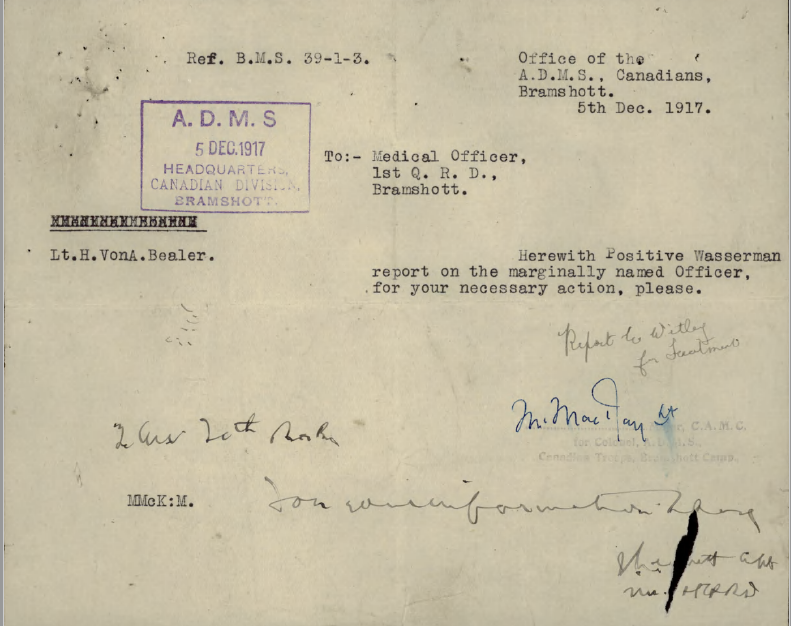

What ever the case, Lieutenant Bealer’s health was to take a turn for the worse. He was ordered to November 17, 1917 to attend to No. 12 Canadian General Hospital for a Wasserman test, a test used for the detection of syphilis. On December 5, 1917 a letter to the Medical Officer, Quebec Regimental Depot indicated the tests where positive and the necessary action be taken regarding Lieutenant Bealer.

This action involved Lieutenant Bealer being assigned to attend the Connaught Hospital, Aldershot for further treatment and was subject to three treatments of Kharsivan Injection, which was also know as Salvarsan treatments, an early effective form of treatment for syphilis. A description of the treatment gives an idea of the nature of the cure and how it was treated at that time:

“Salvarsan was the first organic anti-syphilitic. It was distributed as a yellow, crystalline, hygroscopic powder–one that was unstable. This naturally complicated administration, as the drug needed to be Salvarsan dissolved [1]. The suffering patient would lie face down. Salvarsan, melted in a vacuum with a small amount of methyl alcohol, is mixed with 25 c.c. distilled water and two c.c. of 1/10th caustic soda. The acidic solution is injected into each of the buttocks “deeply, slowly, and gently” [2]. The injection is described as horribly painful, the pain sometimes lasting for six or more days and narcotics were sometimes used to control it.”[v]

Lieutenant Bealer had three such treatments. One on his admission to hospital on December 20, 1917 and then further treatments on the 24th and 27th. One can imagine from the description above the nature of the treatment and the pain he experienced. Couple with the fact the social stigma and future medical impacts of he was to suffer secondary and tertiary syphilis symptoms.

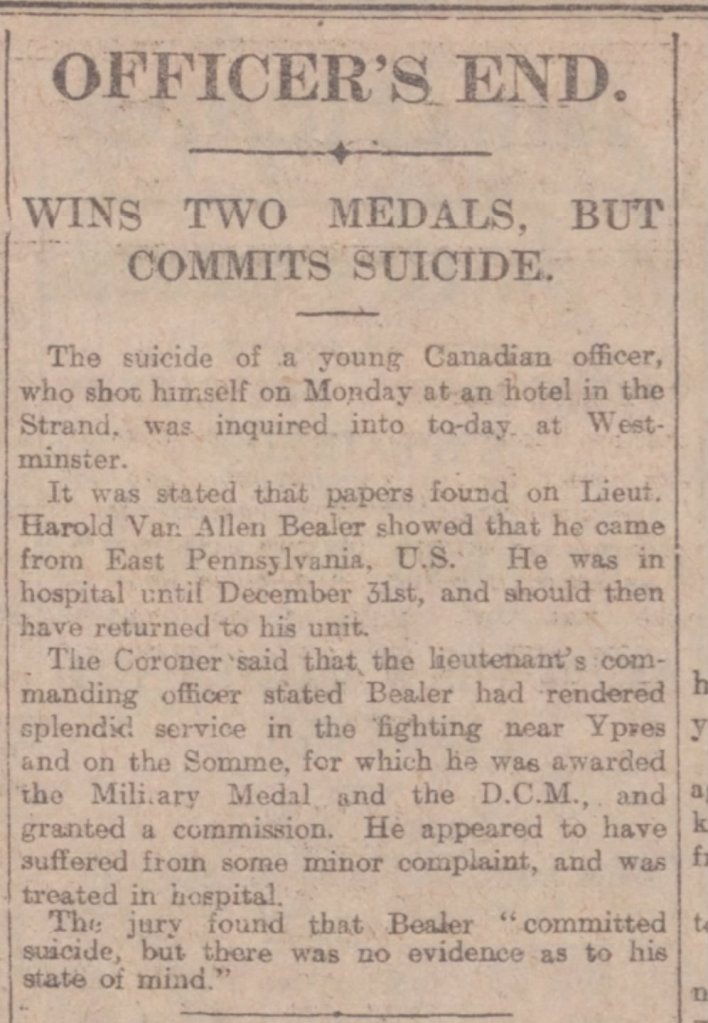

After this experience Lieutenant Bealer was released from hospital on New Years Eve Day and his whereabouts and actions are unknown until his body was discovered at 11:00 A.M. on January 11, 1918 in room No. 36, Haxell’s Hotel, The Strand, London with a bullet hole in his chest. He had committed suicide.

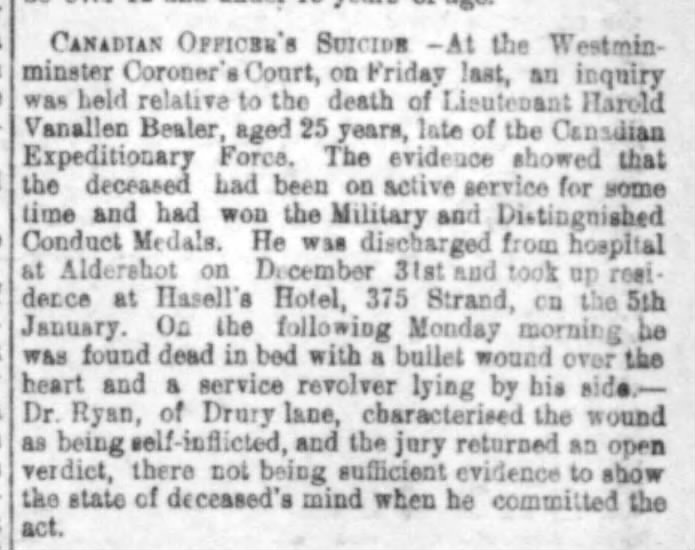

The outcome of the Coroner’s Inquest determined:

“…that the said Harold Vanallen [sic] Bealer did kill himself but there is not evidence to show that state of his mind at the time…”

Yet, there is a cryptic notation in another document in the service record. In the “Report On Accidental or Self-Inflicted Injuries” the Commanding Officer’s opinion as to whether the man was to blame the following is written – “Ill health and finances.”

Thus the mystery of the circumstances of Lieutenant Bealer’s death becomes more poignant. What information or insight did the commanding officer of the 5th Reserve Brigade have to indicate this? The report is dated March 7, 1918 three months to the day after Lieutenant Bealer’s suicide.

Whatever the case Lieutenant Bealer’s home town newspaper, the Easton Free Press ran a series of stories in response to his death and the details related in these news articles do not broach on the actual cause of death as it appears that the information communicated to the family connected his death from a different, more acceptable cause.

The first article appeared on January 9, 1918 and is transcribe below:

HAROLD BEALER, WITH CANADIAN FORCES, IS DEAD[vi]

Eastonian, Wounded in Action, and Invalided to British Hospital, Passes Away

WON MEDAL FOR GALLANTRY

Son of Late Fred Bealer, of This City, Was One of Four Americans[vii]. All Now Dead, Who Met at Montreal and Enlisted For the War At the Same Time.

Lieutenant Harold V. Bealer, D.C.M., Company B, 42nd Battalion, Royal Highlanders, an Easton boy, son of Mrs. [Bealer] and the late Fred Bealer, who [was] probably the [first] Eastonian to [participate] in [the] European war, is [dead] in a [hospital in] England, according to a telegram received by his brother D. Van Allen Bealer, of 241 Ferry [Street], this morning. The [young] man was 24 years of age and is survived by his mother, [brother] D. Van Allen Bealer, and [a sister Miss] Lucy E. Bealer, both residing with [their] mother at the Ferry Street Address.

Lieutenant Bealer was a member of [Lehieton] Lodge. I.O.O.F., of this city and the first member of the lodge to meet death [in active] service during the war.

Lieutenant Bealer had established an enviable reputation in the war and had won [two] medals, the D.C. M. or [Distinguished Conduct Medal] and the [military medal] for conspicuous bravery. He [illegible] in the trenches, went [illegible] many [of] the great battles [illegible] [and] was wounded in the [shoulder] [illegible] the piece[s] of shrapnel [imbedded themselves in his body]. These pieces were [not] removed and [it] is thought the they may have undermined his constitution. What caused is death is not known and the arrival of a letter giving the information is anxiously awaited [by the] grief stricken mother and family.

Young Bealer was anxious to get in the war from the time it started and after making inquiries at the British Consulate in Philadelphia he went to Montreal [where he] enlisted in the 42nd Battalion, Royal Highlanders on April 9, 1915[viii]. He was sent to the training camp at Folkstone [sic], England where his military training [was complete] and [illegible]… No Man’s Land and [illegible] captured a German [sentry] and [brought him back to the English lines. [For this] exploit he received the Military Medal and was sent to England as a reward.

He then made an [illegible] to secure a commission but being an American which had never attended a military school, was unable [to], but set about at once to [illegible] to secure the coveted position. He went to France for a few weeks and then returned [to] military school in England and, after completing his course there, was commissioned as a first lieutenant. He then was sent to a convalescent hospital in Cambridge, England, more for rest than anything else and then went to Trinity College where he took a course in tactical warfare. He was then sent to Shoreham, and since that time has been engaged in training soldiers for service at the front. He was apparently in fairly good health, but on the sixth of December, which was the date of the last letter received from him by his mother, he said he was ill with tonsillitis.

A letter written on December 16 by friends in England, whom Lieutenant Bealer often visited, stated that he was going to a hospital the next day but not for anything [serious]. Therefore, he was admitted on December 17. His death occurred on the 7th of January.

While in England he played in a baseball game between Canadians and Americans which was attended by the King [illegible] and many titled personages. However [illegible] enjoy the [illegible] and made [fun?] of the American pastime.

The telegram [illegible] received this morning reads as follows:

“Ottawa, Ont. Jan. 8.

D. Van Allen Bealer

241 Ferry Street, Easton, Pa[illegible] Deeply regret to inform you Lieutenant Harold Van Bealer, infantry, officially reported died January 7, 1918. Letter follow.

Director of Records”

Lieutenant Bealer attended the Allentown High School and after his father’s death, assisted in managing the latter’s business. Later he retired from this and tough up drafting. He was employed in this work [at Bethlehem Steel Company] and [then] Ingersoll-Rand Company. While in [service he] was frequently requested to do this work, but he preferred the more risky business of fighting in the trenches and insisted on “doing his bit” with his comrades.

A second story followed on the first with more biographical details[ix]:

HAROLD BEALER’S DEATH DUE TO BATTLE WOUNDS

Eastonian’s Name Appears in Canadian Overseas Casualty List

“EIGHTEEN” UNLUCKY NUMBER

Mother of the Young Hero Who Laid Down His Life That World Democracy Might Triumph, Considers It So By Reason of Her Experience – – Little Help Getting Body Until After War.

Associated Press Dispatch to Free Press.

Ottawa, Jan 11. – Lieutenant H.V. Bealer, of Easton Pa., is mentioned in today’s Canadian overseas casualty list as having died of wounds.

--

Mrs. Fred Bealer, the young man’s mother, when shown the above dispatch this morning, said that only Thursday she had learned from a friend of her son in Easton that he had written a letter, later than the last one she had received, stating that he had spent three months in hospitals and that he had blood poisoning.

This was news to Mrs. Bealer, who had no knowledge that her son suffered from this trouble. However, she did know that he had had trouble with is back, as the result of shrapnel wounds, as he barely mentioned in on of his letters that his back didn’t hurt as much as it did.

Mrs. Bealer believes his injuries were much worse than he ever told her, and the he made light of every trouble, so that she would not worry. The pieces of shrapnel had lodged in his shoulder at the time he was wounded at the Battle of the Somme, where never removed, as far as Mrs. Bealer could learn, and it is believed that these pieces of metal caused his last illness which resulted in his death.

The number “eighteen” seems to be unlucky for the bereaved mother of the young lieutenant. It was on the eighteenth day of the month that her husband died; it was on the eighteenth that her son enlisted in the war[x]; it was on the eighteenth of the month that she received the news he was wounded[xi], and when someone mentioned that this as 1918, she had a premonition that something would happen and on the ninth day of the year she received word of the death of her son.

Mrs. Bealer has communicated with the Canadian authorities in regard to having her son’s body returned to Canada, so that she could secure it for burial her along side that of his father, but she has received no word from the Canadian officials yet. However, Canadians in the vicinity, who are familiar with the conditions existing in their country say that there is little or no hope of getting the body back, and it will probably be interred in England and the grave marked, and that she will be able t bring it back to this country for burial after the war.

The third, and last article relates to a letter sent to Lieutenant Bealer’s brother by the Chaplain who served at the funeral:

LETTER FROM MINISTER WHO BURIED LIEUTENANT BEALER

Writes of Military Funeral Honors Given to Brave Young Eastonian Now at Rest in London

The following gratifying and sympathetic letter has been received here by the family of the late Lieutenant Harold Van Allen Bealer who died in London by the effects of wounds, being addressed to his brother:

No. 354 Highbury Park

London, NorthJanuary 17, 1918

Mr. D. Van Allen Bealer

No. 241 Ferry Street

Easton Pa., U.S.A.Dear Mr. Bealer,

It is my sad duty as a (Presbyterian) Canadian Chaplain to write you of the burial of your brother, Lt. Harold Van Allen Bealer. He was buried by myself today at Brookwood cemetery, which is twenty-eight miles out from the Necropolis [?] Station, near Westminster Bridge, London. This is a beautiful country cemetery, where all our Canadian boys are buried who died in London. It is filled with trees and flowers and English heather. Your brother is buried among our Canadian offices and his name and rank are painted on a white cross at the head of his grave. So it will be easy to find the grave should you ever visit this country. He was buried with military honors, there being a firing party of forty-five men who fired three volleys over his grave, after which the bugle sounded the Last Post, and then we came away and left his body to rest in peace in one of the prettiest spots in England.

I never had the privilege of meeting your brother and I do not know the particulars of his death, but I do know that he was the bravest soldier, having won both a military and Distinguished Conduct medal. The officers who knew him best spoke very highly of him, and said that while in battle he learned to be afraid of nothing. He had been wounded three times. He nobly risked all for the sake of others, that they might enjoy freedom and peace, and his spirit is now in the hands of a God, not only wisdom and justice, but also a God of infinite mercy and love, and we know the great judge of the Universe will do right. The number of his grave is 180394.

Assuring you and all his relative and friend by deepest sympathy in your affliction I am

Very sincerely yours,

Andrew D. Reid[xii]P.S. – His nearest friend, Lt. Gee, was at the funeral and told me he would write you.

A.D.R.

The news articles are a better remembrance of the young American that came to Canada to serve in the Imperial Forces than the grim reality of his service record. They also bring him to life by showing that he was an attentive son with his letter writing and his interests involved being involved in activities to encourage the moral and camaraderie between British/Canadian soldier and the newly engaged American Army soldiers.

The harsh truth of Lieutenant Bealer’s war record lays bare the romanticizing of the news articles but their terse dates and fact dehumanize him as well.

[i] 42nd Infantry Battalion War Diary Transcription; page 54; CESFG Study Group

[ii] The London Gazette; February 13, 1917; Supplement: 29940; Page: 1571

[iii] The 20th Reserve Battalion was designated to reinforce the 13th and 42nd Battalions and absorbed the 148th, 171st, and 236th Battalions. It also trained these battalions. There are no online images of this battalion’s diary available at this time.

[iv] World War 1: Chiseldon training camp’s soldiers with VD; BBC News; author Jerry Chester.

[v] Of Syphilis and Salvarsan: The danger and promise of a cure

[vi] Easton Free Press, January 9, 1918.

[vii] Not able to determine at this time identity of other men.

[viii] April 19, 1915 is the correct date.

[ix] The text of the scan is of very poor quality which made accurate transcription difficult.

[x] Attestation papers show Bealer attested in Montreal, Quebec on April 19, 1915.

[xi] Service record indicates he was wounded September 14, 1916.

Discover more from History of the 18th Battalion CEF, "The Fighting Eighteenth"

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

GSW was commonly used for a wound caused by a projectile (or fragment of), so there’s no real contradiction between the two reports

Thank you David. I have to state that having read over 500 Canadian service records the medical records tend to indicate the difference between a gunshot and shrapnel wound. In the case of this soldier I believe you may be correct as the records is summary of medical history. Sadly, the actual file(s) and notes from the injury for Bealer are not in the service record.

I’m more familiar with British records where full medical notes are almost unheard of (even if a record of any sort survive!s)

David,

The quality of medical records in Canadian service files varies from non-existent to detailed hand-written (sometimes typed, esp. if they are medical discharge documents) and I would recommend seeing this post as an example The Wounds of Private Blue . Private Blue’s service record is available to download.

Thank you for all the information, If he is not on the town/city memorial he should be even though he served in the Canadian armed forces.

SJC

SJC,

Thank you so much for visiting and reading. Do you have a connection to Lt. Bealer?

If the original article above could be reproduced in a larger scale we could probably figure out many of the illegible words.

As for unlucky 18, notice that those are the first numbers of his grave registration!

Rob,

Thanks for the suggestion. I have viewed the original scans and increasing the size of the text causes the quality to drop. Plus the scans of the following parts of the article, quiet literally, have the text missing. If you want to see the original document please go to this link. The article is on pages 1 and 5.

I thank you for writing about Harold Bealer. I look after the flags and flag holders on the graves of veterans in Easton Cemetery. I found a large planter/urn with a very tarnished copper name plate named to remember Harold V Bealer. It is located next to the graves of his parents, brother and sister-in-law. I took the time to clean the plate and put a protective finish on it as well as cleaning the urn and leveling it. I’d be happy to share pictures if you are interested.

Jonathon, you comment and efforts are much appreciated. I would love to get those photographs. Best way is ebd.edwards {at} gmail.com.

Eric, I did find that Harold Bealer also had an oak tree and a bronze plaque in a grove of trees planted in the early 1920s in Upper Hackett Park in Easton. Did you get the other photos I sent?

Best Jon Prostak

I did, thank you very much.