| This is a transcription of a biography written by this man’s daughter, Barbara Joan (Routly) Spruce. The original document is typewritten and was scanned and accessed at Family Search. The document scan is deprecated and difficult to read in some places. An attempt has been made to be faithful to the author’s version so spelling, grammar, and other issues exist in the page but it is felt that an attempt to maintain the authenticity of the document helps the context in which it was written. It is a fascinating look into the life of an immigrant from England who lived most of his life in Canada and served his country in both World Wars and his personality comes out in the following pages. |

William Frederick Routly

By

Barbara (Routly) Spruce

William Frederick Routly was born January 21, 1896 at 16 Courtnell Street, London, England. His father, William Henry Routly had done a little farming for his own father, but his real interest and inclination was as an itinerant Methodist lay preacher and he walked over half of England taking services. His father, without sufficient research, bought a hotel in an area no longer fashionable. When he lost his investment, there was not only immediate financial difficulties, but there would be no mortgage backing or inheritance to his sons.

So William Henry had neither a trade he could turn to nor property. In his forties he married a widow, Fanny Ferry, who had two daughters, Lily and Edith. William Henry and his wife opened a coffee-house on Tottenham Court Road in London.

William Frederick was their first-born, followed by John on Feb. 9, 1897, and Sidney on Dec. 18, 1899.

Young William recalled that the restaurant was heavy and ‘old-fashioned’ in appearance with much dark woodwork and heavy carved legs on the table and chairs. The tables were long, banquet style, and he remembered how he liked to drink the vinegar set out upon them. He used to bother the cook until the latter would snatch up the carving knife and give chase threatening all the while to cut “cut his narrative off”.

About 1901 the three little boys were motherless. William was sent to a “semi-military” boarding school. Fanny, was the business head of the pair, and without her, the restaurant was rudderless. By 1908, the business had failed and William Henry brought his sons to Canada to his brother Frederick Routly of Alvinston, in the hope of finding a future on the land.

Young William found life in rural Canada much different from anything he had known. At first they stayed with Uncle Fred and Aunt Lizzie, who was the real boss of the house, and though tiny, ordered everyone around with a will. However, if things did not the way she wanted, she had an interesting knack of being able, or perhaps, through frustration, fell into a fit which would frighten the family to such an extent that she would then get her way.

The farm, while it could use extra hands in harvest times could not support steadily four extra mouths. So as soon as each of the cousins from England could earn his keep as a hired hand, and a place was found, off he would go. By the time he was twelve, William was able to do a man’s work – and he did it. He was permitted to go to school when he wasn’t needed on the farm but there was little continuity to his education in the one-room school, that he never graduated from grade school, and was all through “schoolin” by 14. However, he loved to read. He came, eventually through prolific reading and a passion for lively discussion, to be a self-educated man.

Laura, Will’s favourite cousin married Colin Leitch of R.R. 4, Thorndale, Ont. They invited Will to be their hired man, and as Colin was the sweetest tempered, mildest, gentlest man will had ever met, he was please to leave Glen Rae, a hamlet near Alvinston, for their farm.

Jim Billington[i], a graduate of an agricultural college in England arrived in Thorndale May 3, 1909, staying with a Mr. McGuffin. On May 9, he took a job at Ray Bott’s as a hired man begging work the very next day. The farm was just down the road of the Leitches.

Of course Will and Jim got to know each other, as hired men were loaned out on slack days in return for the neighbour’s had when he was needed.

In September 1914, will went into London for the Western Fair, and me his younger sister, Florence Billington. Will said later, that Jim built such a fantastic picture of his sister’s charms in Will’s head, that Will was disappointed when he finally met Flo.

The summer of 1915, in answer to posters hung in public places, Jim and Will went to “the West” to work in the harvest. The train was slow hot and stuffy. If the windows were open, one was black with soot. Some of the “harvest specials” were permanently open, and were jammed with young men who had paid something like twenty dollars for a ticket. Will’s destination, Yorkton Sask.

They worked in fields so large that the binder would make only one circuit of the field before noon. They worked with others whose language and customs were different. Their only thing in common was an interest in the good wage they expected to earn. Fights among the hired men were common. On one occasion Will was loaned to a farmer who was still living in a sod hut. Their entire home one small room for the whole family. It was said these sod huts only leaked when it rained.

Will returned to Leitches. They had milk cows and the milk was brought into London every morning. One of the first snows of the winter, Will took the milk in the sleigh, but he got a ticket – infraction? – not having bells on the horses. It was dangerous of course, because of the snowy roads, you couldn’t hear the sleigh coming.

In the summer of 1916, Will and Jim joined the army.[ii] Why” “I donno” he said with a shrug of his shoulders. “It just seemed like the thing to do.” “I don’t think we even discussed it, we just went into town together and signed up.”

At drill with the 142nd Battalion at Carling Heights (Wolsely [sic] Barracks) Will was asked what outfit he was with previously. No “outfit” he had learned to drill at boarding school as a child.[iii]

On July 8, 1916, they were sent to Camp Borden for Training before going overseas. A huge treeless area, the ash from burning the trees off lay thick on the ground, and was stirred by thousands of feet.

Gen. Sir Sam Hughes was coming to inspect them before their departure. To please his eye, and not in the interest of comfort, the soldier were to were winter uniforms and carry no waterbottles. The march past would take hours, the ash would be stirred like smoke, the men would be black and parched. They mutinied.

They just stayed in their tents, with one mind. They did not answer the bugle call to form up.

Finally someone was sent to the find out what the men wanted. Summer uniforms and water bottles. Granted. The bugle called them, and they came. And it was a stirring march past. Sir Sam sat like a statue on his horse, and the men in the rows of two hundred passed by him over the black plain. There was no punishment.

They saw the last of Camp Borden on 0ctober 7, 1916 and on November 1st left Canada for England on a troopship. Will was seasick, and he spent [almost] the entire trip on deck, where he lived exclusively on water-ice wafers. Fare for the troops below decks was enough to bring on another bout, so Jim found his way to the officers mess and swiped a roast chicken for his buddy to eat on deck. The voyage took 12 days.

In England Will was awarded a lance-corporal stripe, which he was afraid would keep him from going to France – and seeing action with Jim. One of the men refused his clean-up order, so Will had to report him, as he reasoned that day, and he explained years later, had the private not been reported, he would have been able to refuse future orders, the successful insubordination of one would become apparent to all, and the corporal would have lost control of his hut. In the army, where the success of a project as well as men’s lives are at stake, there must be discipline. The offender was put “on orders” which probably meat pack-drill. And Jim was angry with Will, writing home to Canada to complain about his heartlessness.

Serving at chowtime was meager. Jim said he was always hungry. The men complaining among themselves decided that they had a legitimate beef and that someone should go to the officer in charge and state their case. Will was the one to go. Taking his plate as it was served up to him, he presented it with the question, “Do you think this is a meal for a man?” It must have been the right approach, there was more to eat after that.

It was Friday the 13th of April 1917 when Will, issued two meat sandwiches for 48 hours rations was sent to Southampton en route to France. They embarked at 4 a.m. the next morning. Almost immediately, Jim Billington, their friend from London, Sterling Campbell[iv], and Will Routley, being at opposite ends of the alphabet, were separated. On May 28 Jim was “killed in action”, but for weeks, the family received conflicting official reports that he was “missing”, “wounded and in hospital” and on June 24 Flo was still writing to him, believing him to be in hospital somewhere.[v]

It was at this time that Will developed a fatalism, he said he carried all this life. For in a group, a shell would hit, and some would be hit and others spared for no apparent reason. He came to the conclusion, if you “number is up” it is up.

France was a mass of trenches, and one could walk miles without ever poking your head above ground level. Will remembered one work detail on which they were bringing shoves and barbwire along a road in the middle of the night. A shell fell in front of [them], another behind them, ..the next would.. “Hit the ditch” someone cried, and sure enough somewhere a big gun was finding their range, and the third fell among them.

On another occasion, Will was bringing several men as replacements for a machine gun emplacement. They walked all night. First they had become lost, and walked until the trenches petered out and listening they could hear voices speaking German – they were in no man’s land. Beating a hasty and silent retreat, by the time they found the handful they were relieving, the sun was about to come up and the officer in charge was holding the men to their gun at pistol-point. You can imagine how relieved they were to see their relief.

Cold, wet, muddy, hungry, thirsty and lice-infested, the men spent their spare time, as Will recounted, in picking off lice and dropping them onto a hot piece of tin held over a candle. There was no other way to get rid of them – short of cleanliness, and there wasn’t any of that. Wood for boiling tea was in such short supply that coming back from the front one day, Will picked up a piece of wood and carried it for miles thinking of the nice little fire he would make with a little water from a puddle. More thirsty than hungry, their ration not having reached (too close to the front), all Will had was a crust of bread to dry to even bite. However, he softened it in a puddle, sucking the dirty water from the bread and eating the bread when it was soft [enough] to chew. “And I didn’t get sick from it, not a bit,” he marveled years later.

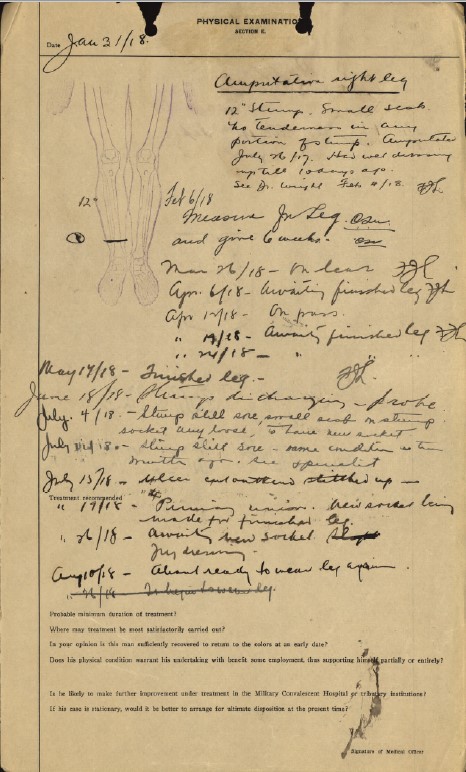

On July 19, a piece of shrapnel hit him on the top of the foot. Will emptied the contents of his first-aid kit iodine in the wound and bound it up as best he could. He had to wait all day until he could be carried out of the trenches under cover of darkness. The foot was amputated in France and Will was sent to recuperate at St. Leonards-on-Sea[vi]. Still wondering where Jim was, Will wrote to Flo from this English hospital saying that he had now been in bed 17 days, somewhat broken by journeys between hospitals. Flo replied on Aug. 29 that Jim had been killed when an enemy shell landed near him.[vii]

The night before the hospital ship sailed for Canada, there was no passes issued for any of the soldiers being invalided home. Not to go into the town and bid goodbye to the families and friends who had made the boys welcome during their weeks and months of recovery was unthinkable, and they all hobbled into the town. Again there was no repercussions – after all, if the had been CB (confined to barracks) would the ship have sailed empty. The ship berthed at Halifax on Jan. 10, 1918.

By March 21, the prosthetic department at Davisville Military Hospital, Toronto had fitted Will with an artificial leg “in the rough”. For her birthday on April 23, Flo received a gold watch, Will having left the parcel previously with her mother. On May 18, Will went gaily downtown to celebrate the mobility of the new artificial leg. The unaccustomed pressures on the stump brought a painful end to the jaunt. He returned to suburban Toronto by streetcar, leaning on the shoulder of his chum.

On October 8, 1918, he got his honorable discharge, and that month received his first disability pension cheque of $20. By the end of the following month, he had taken and quit a job with “Multigraph”[viii] in Toronto. As he explained it years later, he was undergoing “a period of adjustment” in which he didn’t know what he wanted to do, where he wanted to work, was easily irritated, felt restless, and not only lacked inclination and direction but refused to listen to advice. He returned to Colin and Laura Leitch’s, R.R. # 4, Thorndale.

On January 14, 1919, as the great ‘flu’ epidemic began to wane and the people of London began to think they had survived it, Alice Billington, who had gone to the Grand Theatre without rubbers through the rain and snow, contracted the ‘flu’ and died. In those days, to kill germs, the rooms were scrubbed with [word missing] and afterwards, sulphur burned. Alice’s steady boy-friend “steered clear of the place” at this time, but Will came in from the farm and helped Flo’s mother with this chore.

Will got a job with the Ford Motor Company in Ford City[ix], (now part of Windsor, Ont.) At first he had a job as a machinist, but there was too much standing, and then he got a job as a dial-watcher in the “heat-treat” plant. He had previously turned down the offers of friends and relatives to back him in the veteran’s farm loan because he knew the leg just couldn’t stand up to days and days of walking on uneven ground.

On August 1, he came up by train to London, and met with Flo. They left his suitcase with a storekeeper while they went shopping, but Will was positively in a fret about his bag. Flo wondered why he was being such an old woman about his belongings, and they soon returned to pick up the suitcase and go to the Billington home. The reason for his concern became immediately apparent when Will present Flo with a diamond engagement ring that he had brought in his bag.

After Flo received her diamond, several girls at the “Bell” where she worked as an operator, got theirs. Florence revealed in a letter that she was glad she didn’t choose her own as she “would have felt she should be economical”. She liked the “modern setting” (tiffany) that he had chosen. (The ring had cost Will $100.)[x] The wanted to be married October, but Flo’s mother persuaded them to wait for Christmas.

Florence left the Bell on Dec. 13, and Will and Florence were wed on Dec. 25. 1919. The ceremony performed by H.B. Ashby at St. Matthew’s Anglican Church, London, Ont. Beatrice Mood and Bernard (Bert) Hawkins were the witnesses.

Will had purchased a house on Hall Avenue[xi] in Windsor, and furnished it with a fumed oak dining suite, an oak library table, a wicker lamp, a painted bedstead and dresser among other things.

In an age when “nice girls didn’t talk about such things” and Samuel Billington’s advice to his daughter had been a gruff “if you get into trouble young lady, don’t darken our door again”, Florence came to marriage in appalling ignorance. Hannah Billington had admitted to her daughter that “This is the day, I should be telling you something, but I don’t know anything to tell you. And that’s exactly what my mother told me when I got married”.

Florence was under the vague impression that it would take about two years for a marriage to progress to intimacy, and “well, if it doesn’t work out I will get a divorce,” she had assured herself blithely. Someone had made a remark at the wedding supper as someone is always prone to do on such occasions, that planted a seed of doubt in her mind, about her understanding of such thinks. Going down to Windsor that night on the train, Flo became quieter, Will related years afterward. “Finally I managed to extract from her, what was troubling her.”

And Florence said many years later, that “he assured me nothing like that would happen tonight, and if it will make you feel any better, I’ll sleep at the kitchen table”. On arrival at their new abode, Will drew up a kitchen chair and lay his head down on his arms at the table. Florence got alone into her bed, but her conscience smote her… it was, after all, his house, his furniture, and yes, even his bed. So she gout up briefly and said, “you may as well come to bed.”

Their first child, a daughter, Marion Florence, was born at St. Joseph’s hospital, London, on Nov. 28, 1920. Florence stayed at her parents’ house in London almost 2 months in total, before and after the event.

A second daughter, Elizabeth Alice, to be called Betty, was Jan. 20 1922 at Grace Hospital (Salvation Army) in Windsor.

During the winters of 1925 and 1926, Will went to night school at Windsor-Warderville Technical School[xii], first taking auto mechanics and then typing.

In 1927[xiii] Will’s father, William Henry Routly died at in the Protestant Old Peoples Home in London (it became the McCormick Home). Colonel Graham of Will’s 142nd Battalion had helped to get him admitted there.

Will and Flo had bought, or were buying on time payments, a model-T Ford Touring car, and made the arduous trip to London a number of times. They naively believe that [Ford’s], though laying off employees due to a slow market, would not lay Will off, who was buying a car.

As a veteran, Will was able to get a job for six months, having passed a civil service exam for a “messenger”, which paid $12 to $14 a week. Then they lived in their house, meeting no payments, trying to decide what to do. While they still had a nest-egg, they decided to buy a place in the country where they could have a cow, some chickens and a garden and manage to eke out a living.

They bought a place in Byron, called Springcrest Farm, moved in May 3, 1928, having turned their backs on, and simply walked out and left their Windsor house. Will who had a latent interest in chickens became a poultry farmer and egg-man.

Perhaps he was interested in chickens and egg production, but he had a real interest in people. He was part of the household for many people and some of his egg customers remained faithful for 45 years. His number of customers would grow when a daughter would marry, and her mother would ask Will to see that at least she got fresh eggs every week. “Mr. Routly” became such a trusted part of the scene that often he would not see his customers for months at a time. Entering the house, if there was no reply to his “Helloo?” he would inspect their “egg bowl” in the fridge, judge how many eggs they would need before his return, –he knew whether they were a dozen-a-week, large, medium or cracked-egg buyers, or two-dozen customers—take the money from the bottom of the bowl, leaving the required change.

On Feb. 12, 1930. Will’s mother-in-law, Hannah Billington died. On July 11, 1931, their third and last daughter was born, Barbara Joan, at St. Joseph’s Hospital, London. Will wrote in an autograph book that year, the times being hard, and money scarce, “I wouldn’t give a [nickle] for another 1931—and at Florence’s remonstrance, added –“except for Barbara Joan”.

Will hatched his own chicks in coal-oil heated incubators in the cellar. The incessant cheeping of day-old chicks sitting out their forty-eight hours in cartons in the signaled the end of winter. Then they would be put out in a freshly-white-washed pan, where they would keep warm under the hood of a coal-fired brooder-stove.

Will was one of the “village fathers” on the township council, representing the police-village of Byron one year. He would get dressed up in his navy blue suit when he returned to “civvies” after the Great War, and now purple with age, and would go off to the meetings.

The couple were also active in the local players. One play had Will as the villain, burning his store to collect the insurance, and this daughter Barbara, ever a [sucker] for a story, was upset at the idea. She asked him afterwards, “in the play, did you really burn your store?” and his reply, “in the play, yes I did,” brought tears.

Barbara, who was well looked after during rehearsals and productions by her older sisters, became ill. Florence, who had been having a lovely time acting in these plays, was conscience-stricken. My place, she said, was at home … and so she dropped out of the players club. It was, of course, unthinkable that Will would continue in a mixed group without his wife, so of course he had to resign as well.

War was declared in Sept. 1939, and not long afterward Will joined the militia, now called the Reserve Army. He trained Wednesday evenings with the Army Service Corps at the Armories on Dundas St. in London. He once spent several days, possibly, only a weekend back at Camp Borden learning to drive heavy vehicles, and he loved it.

Florence’s father, Sam Billington spent Saturdays with the family, Will driving him back on Saturday nights to Bill and Marguerite Billington’s house at 3 Langarth Street, where Same made his home with them. Grandad Billington died in Victoria Hospital in November 1942.

On July 11, 1947, Will’s brother Syd died.

On June 19, 1948, Will got a new grey striped suit, and a secondhand, ten year old Nash –which proved to be a lemon – and gave away his daughter Marion in double ceremony (Betty being given away by Uncle Bill Billington) at St Lukes-in-the-Garden, a non-denominational little church in the Sanatorium grounds (St. Anne’s being under renovation at the time). Marion married William George Face, and Betty, Lloyd Gordon Spearman.

The first of ten grandchildren was born on October 8, 1949. Gerald Lloyd’s safe arrival was a matter of great concern to his grandfather Routly. Will refused to voice his fear in words, but gave every indication that due to his brother John’s having been born with a hare-lip and cleft palate, he was afraid that he might have passed on a week gene.

On Sept. 16, 1950, Barbara married Colin Emerson Spruce (who was never called Colin in his life, but was always as Bud) at St. Anne’s Anglican Church, Byron. Will, by this time, had become confirmed in the Anglican Church.

Diana Marie Facey, the first of five granddaughters was born Oct. 18, 1950.

Florence was ill for almost a year before her death in September 1955.

Except for a brief hospital in April of that year, she remained at home, as was her wish. Will, whose title of Daddy, had long ago mysteriously changed to “Pop” did the looking-after. Although a Victorian Order Nurse eventually came several times a week, Pop was against having any other outside help. “There’s nothing Barb and I can’t manage”. Barbara and Bud had built a house next door. That final summer, the hottest, driest, the area had had in about 18 years, was an endurance test for all. Will slept on a mattress on the floor to be near to hear if Flo wanted anything in the night. When the end[xiv] finally came, he sat with her alone all night, then with dawn went out to do the chores for something to do. Soaked with dew, and desperately needing company he went next door to tell the Spruces.

By this time, the grandchildren were Jerry Spearman, Diana Facey, Peter Colin Spruce, Rosemary Verlie Face, David Charles Spearman, Andrew William Spruce and Ellen Elizabeth Facey.

Pop found companionship with his daughters and their husbands and diversion in his grandchildren. Twice a week he had supper in the Glanworth, Ont. homes of Marion and Betty. The rest of the evenings he ate with the Spruces. He became something of a social lion with his egg-customers suggesting dates, if not marriage with their mothers, grandmothers, aunts and even themselves. But Pop confided to his family that Flo’s illness had been too much, “O simply couldn’t go through that again with anybody”. So when he wished a lady to escort to some function, he asked one of his daughters.

Accustomed to a family of females, Pop enjoyed the conversation of women. And his egg customers enjoyed his interest and his willingness to be a sounding-board for their ideas. [Charoltte] Hawthorne, a customer who looked on him as a father-figure once said, “I don’t care if you bring cracked eggs, stale eggs, blood-spot eggs, or even rotten eggs; just so long as you come – you are so much cheaper and more satisfactory that a psychiatrist.”

As he began to try to cut back his egg route, more people clamored to be included. As his financial need was less, so he became more selective. One woman in Byron admiring the eggs of a customer, said “I wish he’d bring me eggs.” “Just ask Mr. Routly, I am sure he will.” “I’m sure he won’t.”

And he wouldn’t. She had been bossy and overbearing at some time during a church project, and egg-customership was not bestowed on the undeserving. He also cropped one long-time customer because after the husband retired, they had too much togetherness, and shrieked and yelled at each other constantly.

Every fall, at Western Fair time, Pop would be down at the Parish Hall making pounds and pounds of hamburger into meat patties, a job which he had trained for by years of hefting eggs and knowing their sizes by weight. He enjoyed it and was enjoyed by the other workers during the 10 days to 2 weeks, for his patience and good humour.

Elected to the board of management of St. Anne’s church, he got back onto public life. However, he liked to spend Sunday mornings with the Professor next door, at which time they solved, over endless cups of coffee, the problems of the world.

Pamela Claire, Derek Arthur, and Lesley Landon were born to the Spruces, much to Pop’s consternation. He felt so many grandchildren was “pressing someone’s luck.” A reluctant and absent-minded baby-sitter, it was soon apparent that bedtime-stories, and curfews and tuckings-in were not where his interests lay.

However, as the Spruce boys, Peter and Andy, got into organized sport, he was a keen spectator. As they acquired increasingly conflicting game locations, Pop was delighted to have the chore of taking a carful of players to and from the rink or diamond. Known as “Pop” throughout the village, he knew and enjoyed the friends of his grandsons, and was ticked when they would sit down beside him in the local restaurant for a chat. He was a local character and loved it.

Son-in-law, Bud, was always warning him not to lean over the boards at rinkside or he’d get hurt. Pop could be dragged back, but he simply couldn’t stay safely back. One afternoon, two players were pressing for the puck they held between them. Of course Pop was hanging over the boards, and one yanked back his stick the other had been leaning on, Pop was butt-ended in the nose. It broke his glasses, spread his nose over his face, broke his upper plate, which in turn cut the upper roof of his mouth. Pop had to be driven home. Barbara took him to Dr. Jack Orchard, who had known him for years… “Good heavens, you’re limping, what happened to you?” “Somebody shot my foot off – but that was 50 years ago,” he pointed to his cut and puffy face, “this is what I am here for.” “And how did you do that?” “In a hockey game it was an accident, of course.”

Well, it was not all bad, it afforded an opportunity to get new glasses and get his teeth checked and repaired, two little chores that he was always too busy to bother with. Pop was also made assistant manager of the hockey team so that in future he would be eligible for team insurance when injured in a game. Delighted with his new title, he took his duties seriously. He earned a crest with his team in a tournament, and resigned from the board of management as their Tuesday night meeting interfered with his games and practices.

When Pop turned 65 he treated himself to the luxury of dropping his Saturday route the he had done conscientiously for decades. This enabled him to take in the Saturday sports events of the season. When he turned 70 he dropped all the customers whom he didn’t enjoy as people. It took him just as long to take eggs to fewer customers, but it was tea with this one, coffee with that, and chats everywhere. It mattered not they paid irregularly, it mattered only that they were congenial and would take the time and were interested in lively discussion.

In Feb. 1973, Pop retired from the chickens. He confided, on his way to the hospital that he had, after fifty years, lost interest in chickens and eggs. For a year following, he was in reasonably good health, reading, talking, arguing, and refusing to think about giving up driving – this last driving his daughters to distraction with worry. Spring and summer found him in and out of hospital several times.

His final hospitalization was a mere 8 days, and he quietly retired from life on August 8, 1974.

[i] Samuel James Billington (1/11/1888-28/05/1917).

[ii] Both men attested on the same day, 7 December 1915 at London Ontario with the 142nd Battalion. Will’s regimental number was 823146 and John’s was 823145. They literally were standing in line beside each other and, as friends, they decided to enlist together.

[iii] Both men did not have any prior military experience.

[iv] Private Sterling Carl Campbell, reg. no. 823416, joined the 142nd Overseas Battalion on 27 December 1915. He would be a technical director for the Oscar winning “All Quiet on the Western Front” (1930).

[v] Private Billington was reported wounded on 13 June 1917. The report stated he was wounded on 28 May 1917. A subsequent report dated 5 August 1917 reported him as “Prev. reported wounded. Now Killed in Action.” Thus, more than 2-months transpired before the family was updated to the actual status of their family member’s fate. His body was found and he is buried at La Targette British Cemetery, Pas de Calais. He was one of 3 men who went missing on May 28, 1917.

[vi] Bannows Red Cross Hospital. He was cared for there from 8 August 1917 until 8 October 1917.

[vii] This soldier’s Circumstances of Death Card simply states, “Killed in Action”. He was killed on 28 May 1917. Initial news reported him wounded on that date and the 18th Battalion War Diary does illuminate the circumstances of his death. He was killed during a German trench raid. One other man was wounded and three went missing during that action.

[viii] Probably the company Addressograph Multigraph, a large business printing concern manufacturing, selling, and supporting printing machines, such as those used to print business cards.

[ix] Walking Tour of Ford City.

[x] Equivalent to about $1,550 CAD in 2023 money.

[xi] 657 Hall Avenue, Windsor, Ontario according to his service record.

[xii] Windsor-Walkerville Technical School.

[xiii] Actual death was 17 December 1926.

[xiv] Florence Billington died on 2 September 1955.

Discover more from History of the 18th Battalion CEF, "The Fighting Eighteenth"

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a comment